When Constitutionalism Becomes Comedy

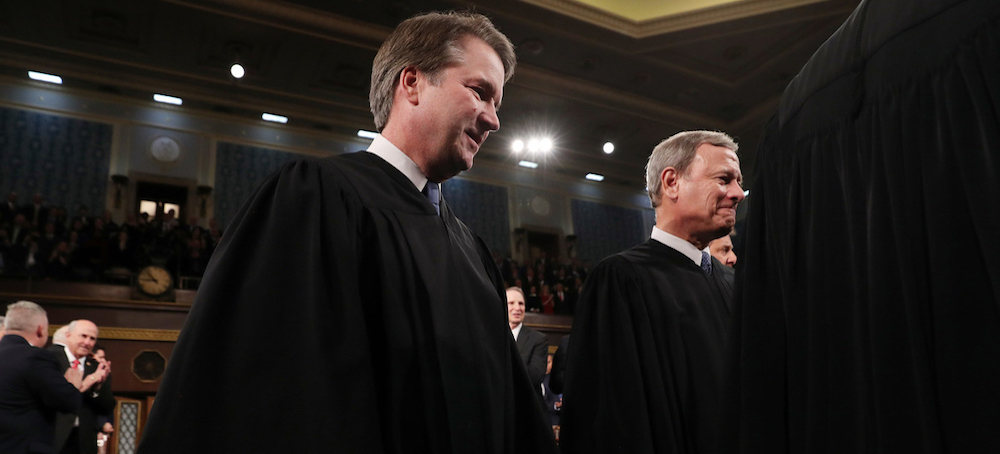

Timothy Snyder Substack Justice Brett Kavanaugh and Chief Justice John Roberts. (photo: Getty Images)

Justice Brett Kavanaugh and Chief Justice John Roberts. (photo: Getty Images)

We stand on the threshold of comedy already.

A Supreme Court justice takes big gifts from people who have an interest in Court rulings. Morally shocking, but also ludicrous.

The Court responds by ignoring a fundamental principle of justice: that one cannot judge oneself. This is tragic, but also funny.

The wife of that justice supported the overthrow of Constitutional rule during an attempted coup. It’s hard to miss the humorous side of that.

She urged the president (through baffling texts to his chief of staff) to (among many other things) "release the Kraken." This is horrible in its totality, but hilarious in the detail.

She attended and helped organize the rally that became the assault on the Capitol on January 6th, 2020. And she helps run a for-profit consulting firm that takes money from people who have cases before the Supreme Court.

In a Court wishing to maintain a veneer of seriousness, Clarence Thomas would recuse himself from cases where Ginni Thomas is making money and from cases concerning Trump's insurrection.

Thomas did recuse himself from a single case that touched on January 6th, when doing so did not matter. That’s distressing; but it’s also amusing to consider that he thought he was fooling anyone.

What is left for Supreme Court justices at this point is an overt commitment to legal theory. Most justices, Thomas included, are "originalists," and indicate that they are bound, in their rulings, by doctrines known as intentionalism or textualism.

In intentionalism, the Constitution is held to mean what its framers intended it to mean. In textualism, the Constitutionalism is held to mean what its plain language indicates. These views are what most justices want us to take seriously. It would help if the justices who propound these views would act consistently with them.

Court rulings favor big business and make it harder for people to vote. We are assured that this a side effect of intentionalist and textualist readings of the Constitution. It is mere coincidence, we are told, that these rulings align with the interests of the political forces who organized the justices' education, ascent, and appointment. Perhaps this is true. Perhaps it is coincidence. Perhaps textualism and intentionalism mean something.

Or perhaps it is all a sham. We are about to find out.

The Supreme Court is about to consider Anderson vs. Griswold, the Colorado Supreme Court ruling that Trump may not appear on a primary ballot.

This is a case made for a textualist or an intentionalist.

For a textualist, intentionalist, or originalist of any sort, Anderson vs. Griswold is utterly simple. The text of Section Three of the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution forbids insurrectionists such as Trump from holding office. The intentions of those who discussed and formulated Section Three of the Fourteenth Amendment are similarly clear.

This is where the comic potential emerges. This Court is unlikely ever to hear again a case of such simplicity, in which the text and context of the Constitution so obviously demand an unambiguous verdict: to confirm the Colorado ruling.

If the Court does otherwise, it will look silly.

But three of our textualists and the intentionalists were appointed by Trump, and silliness seems to be the general expectation. The theory of Trump's lawyers, as one of them has actually said out loud, is that Supreme Court justices appointed by Trump belong to Trump.

The tittering has begun. Like an audience that sees the banana peel on the stage, commentators goad the justices towards the pratfall. It is widely proclaimed that the Court's decision rule should not be the Constitution, but instead the psychological state of Trump supporters.

“Maybe folks’ll be upset” would indeed be a funny way to decide a case.

Such a pitchfork ruling, a judgement based not on law but on guesses about the moods of strangers, would be as far from intentionalism and textualism as the justices could get. It is just the sort of thing that intentionalists and textualists say that they never do. Their heroic pose is that they must do just what the Constitution says, regardless of the consequences.

After a pitchfork ruling, the entire originalist pretence — that justices stand bravely apart from the moment and evaluate the text or context of the Constitution as they must — would dissolve.

The consequences of courting ridicule are, of course, very serious. Our form of government depends on a balance between the executive, the legislative, and the judicial branches. When such a government is toppled, it is usually by an executive who is able to dominate the other two branches. One way that an executive does so is by mocking the other two branches, portraying them as unnecessary and led by buffoons.

And so actual buffoonery helps no one. If Trump is left on the ballot in defiance of the Constitution by people who claim to be its protectors, he will not respect it or them. But the danger of constitutional comedy is general. It leaves the rule of law more vulnerable, and makes regime change more likely.

PS You might be wondering why you have not heard more about Section 3 of the Fourteenth Amendment. This is because it is not generally taught in law schools. But what is taught or not taught in law schools, what is in fashion or not in fashion in a given moment, should be absolutely irrelevant to the textualists and the intentionalists. The wording of the Constitution itself is as clear as day.