Tim Walz Is a Dream Pick for the Labor Movement

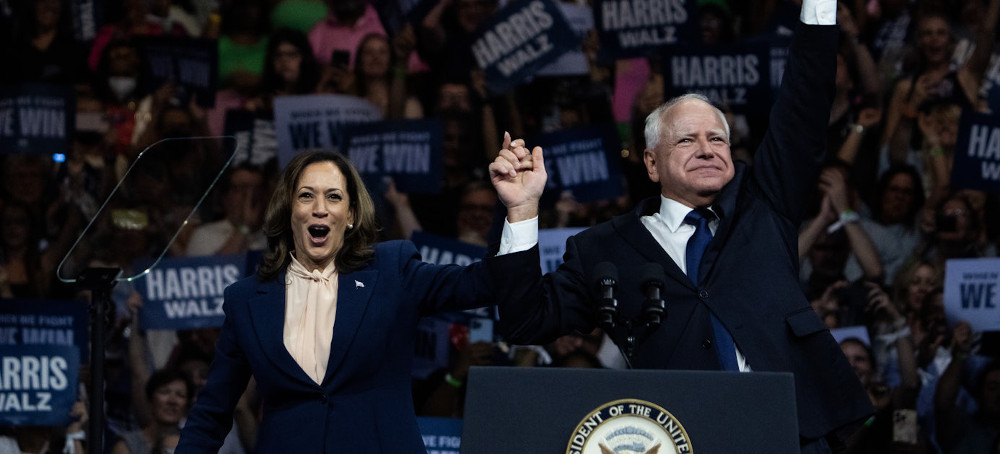

Timothy Noah The New Republic Kamala Harris and Tim Walz make their first appearance as the Democratic ticket, in Philadelphia on August 6. (photo: Tom Williams/Getty)

Kamala Harris and Tim Walz make their first appearance as the Democratic ticket, in Philadelphia on August 6. (photo: Tom Williams/Getty)

He’ll help Kamala Harris make up for lost time courting the working class.

In 2020 President Joe Biden, with an excellent record as a friend of labor, won 56 percent of union households. Two years later, Walz, running for reelection as governor, won nearly 60 percent of union households. In 2020, Biden won 32 percent of the white working-class vote, defined conventionally as white people who lack a college degree. In 2022, Walz won 44 percent.

Much of Walz’s working-class appeal is stylistic. He’s a former public school teacher, which is basically a working-class profession. He’s a veteran. He’s a hunter and a gun owner who, as recently as 2012, was endorsed by the National Rifle Association when he ran for reelection in Congress (where he served from 2007 to 2019). He wears a baseball cap.

Walz has a strong labor record to match. In a July 29 letter urging Harris to choose Walz, 26 Minnesota labor leaders noted that Walz

enacted paid family and medical leave for all families, provided unemployment insurance to hourly school workers, expanded the collective bargaining rights of Minnesotans, provided free school meals to every Minnesota student, appointed a labor lawyer to lead the state Department of Labor and Industry, signed a tough law against wage theft by corporations and developers, and made it illegal for employers to force working people to attend anti-union meetings.

Three days later, United Auto Workers President Shawn Fain named Walz as one of his union’s top two choices for vice president (the other was Kentucky Governor Andy Beshear). “They’ve always been there for working-class people,” Fain said of the pair. During last year’s UAW strike, Walz and Beshear walked picket lines with autoworkers.

The centerpiece of Walz’s labor policy is S.F. 3035, a law he signed in May 2023 that the news website Minnesota Reformer described as potentially “the most significant worker protection bill in state history.” The law requires Minnesota employers to grant full-time workers at least six paid sick days per year; bans noncompete clauses in new employment contracts; bans “captive audience” meetings, in which workers are required to listen managers’ anti-union messaging; establishes a board to set minimum pay and benefits for nursing home workers; extends job protections to meatpackers who refuse work they deem too dangerous; designates general contractors in the construction industry as joint employers jointly responsible for any wage theft committed by their subcontractors; and requires warehouse distribution centers (notably, Amazon’s) to furnish workers with clearer instructions on their expected work pace and also data on how well those workers are meeting those expectations. In addition, the bill allows classroom size in public schools to be negotiated through collective bargaining and extends to early education and adult education teachers the same contract protections enjoyed by K-12 teachers.

Randi Weingarten, president of the American Federation of Teachers, told me that Minnesota has been part of an unsung revival of labor rights at the state level. “There are some states that are laboratories for autocracy,” she said. (She didn’t name names, but these include Florida and Texas, which in the last couple of years passed laws barring local jurisdictions from passing ordinances regulating heat exposure for outdoor workers.) But there are other states, Weingarten explained, that are “laboratories for opportunity.”

Minnesota under Walz, Weingarten said, has been a laboratory for opportunity. New Jersey, she said, is another; under Democratic Governor Phil Murphy, the state last year passed a Temporary Workers’ Bill of Rights that, among other things, requires temp workers to receive pay comparable to that of permanent workers. Michigan, Weingarten said, is yet another. Governor Gretchen Whitmer last year became the first governor since the 1960s to repeal a right-to-work law.

Weingarten compared these labor-friendly states to New York during Franklin Roosevelt’s governorship, from 1929 to 1933, when Roosevelt enacted some of the same labor protections he would later enact nationally as president (through the efforts of the same administrator, Frances Perkins, who was Roosevelt’s state industrial commissioner before she was his labor secretary).

Walz’s achievements on behalf of workers match or exceed those of the governors in Weingarten’s other laboratories of opportunity. Writing in The Guardian, Steven Greenhouse, capo dei capi on the labor beat, praised Walz’s stewardship, under the headline “The Best State for Workers.” In addition to S.F. 3035, in May Walz signed a bill requiring Uber, Lyft, and other rideshare companies to pay drivers a minimum of $1.28 per mile and 31 cents per minute (excluding tips). According to the Service Employees International Union, this constituted a 14 percent increase over the average driver’s 2022 compensation. No other state has established a pay minimum for rideshare drivers. This precedent probably doesn’t thrill Harris’s brother-in-law, Tony West, who’s preparing to go on leave as Uber’s chief legal officer to work on her campaign as “family-member surrogate” (whatever that means).

Walz left Congress with a lifetime score from the AFL-CIO of 93 percent, compared to 90 percent for the average House Democrat. Harris left the Senate with a 98 percent lifetime score, which sounds better but matches the score for the average Democrat in the Senate, where labor bills get voted on less frequently.

“By choosing [Walz] as her running mate,” pronounced International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers president Kenneth Cooper in a prepared statement, “Kamala Harris proves she is committed to continuing President Biden’s pro-union legacy.” That is exactly what the Harris campaign needs organized labor to say about her vice presidential choice. It’s certainly true that Walz is strongly committed to organized labor. At the moment, signs are favorable it will turn out to be true of Harris too.