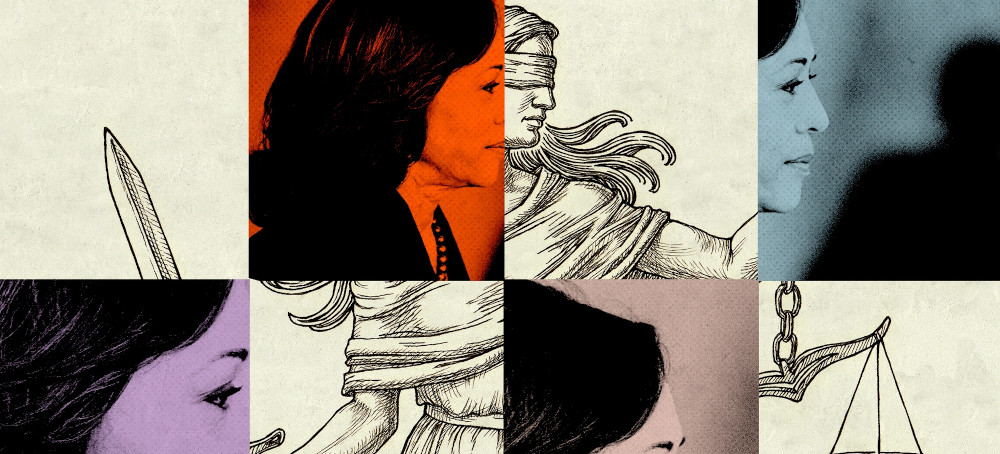

The Prosecutor vs. the Felon

Elaina Plott Calabro The Atlantic Kamala Harris is finally embracing her law-enforcement record, though Republicans see it as a vulnerability. (photo: Bloomberg)

Kamala Harris is finally embracing her law-enforcement record, though Republicans see it as a vulnerability. (photo: Bloomberg)

Kamala Harris is finally embracing her law-enforcement record, though Republicans see it as a vulnerability.

She had no choice, as she launched her Democratic presidential primary campaign from her hometown of Oakland, California, but to acknowledge her past life as a prosecutor. Deputy district attorney in Alameda County, district attorney of San Francisco, attorney general of California—29 years of public service, and 27 of them had been spent in a courtroom. This was her story, and yet not five minutes into her announcement, she was already catching herself as she told it. “Now—now I knew that our criminal-justice system was deeply flawed,” she emphasized, “but …”

Trust me, she seemed to be insisting: I know how it looks.

So it would go for the next 11 months, a once-promising campaign barreling toward spectacular collapse as Harris pinballed between embracing her law-enforcement background and laboring to distract from it. Rather than defend her record against intermittent criticism from the left, she seemed to withdraw into a muddled caricature of 2020 progressive politics—suddenly calling to “eliminate” private health insurance, say, and then scrambling to revise her position in the fallout. By the end, no one seemed to have lost more confidence in the instincts of Kamala Harris than Kamala Harris herself.

Five and a half years later, Harris is again running for president—but this time as a prosecutor, full stop. In her announcement speech on Monday in Wilmington, Delaware, the day after President Joe Biden had dropped his bid for the Democratic nomination and endorsed his vice president to succeed him, Harris heralded her law-enforcement experience without caveat. “I took on perpetrators of all kinds,” Harris said. “Predators who abused women. Fraudsters who ripped off consumers. Cheaters who broke the rules for their own gain. So hear me when I say: I know Donald Trump’s type.” Harris fought a smile as her campaign headquarters erupted in applause.

The enthusiasm seemed only to build as Harris proceeded to tick off her accomplishments as a local prosecutor, a district attorney, and an attorney general. Within hours, Harris had locked in all the Democratic delegates needed to become the party’s nominee; the next morning, her campaign announced that, in the little more than 24 hours since Biden had withdrawn from the race, Harris had raised more than $100 million.

After years of struggling to find her political voice, Harris seems to have finally taken command of her own story. “I was a courtroom prosecutor,” she proudly said to open her next stump speech, in Milwaukee. Just as in Wilmington, she spoke with the confidence of a politician who knows that what she is saying is not only true but precisely what her audience wants to hear. Four years after the fevered height of “Defund the police,” “Kamala is a cop” has a different ring to it—and with the Republican nominee a convicted felon, Harris’s appeal, her allies believe, is now the visceral stuff of bumper stickers: Vote for the prosecutor, not the felon.

Harris’s decision to reclaim her record has seemed to satisfy the many Democrats who have long urged her advisers to “let Kamala be Kamala.” But she still has only three months to rewrite the story of a vice presidency defined by historically low approval ratings. And making her law-enforcement background a key feature of her candidacy will bring renewed Republican attacks on its complicated details.

Of the various factors behind Harris’s sudden acclaim, one might be that her career has finally assumed the tidier logic of narrative. In my time covering her vice presidency, I’ve learned that this, more than anything else, is what otherwise sympathetic voters have consistently clamored for when it comes to Harris: some way to make sense of the seemingly disjointed triumphs and valleys of her tenure in national politics. The voter could be a lifelong Democrat or a Republican disdainful of Trump, but the story was more or less the same. In 2018, they’d been impressed—so impressed, they’d reiterate—by the Senate newcomer’s questioning of Trump’s Cabinet and Supreme Court picks. But then they’d watched her presidential campaign flame out before the first primary vote; then they’d seen her get all tangled up in the Lester Holt interview as vice president; and then, well, they weren’t particularly sure of anything she’d done in office since, but the occasional clips they saw online suggested that things weren’t going well. In retrospect, their initial excitement about Harris had come to feel like something born out of a fever dream.

This confusion helps explain Harris’s historically low favorability ratings as vice president. It is also a key source of exasperation for Harris’s team: Through the latter half of her vice presidency, Harris has cut a more accomplished profile as she’s represented the U.S. abroad and spearheaded the administration’s response to the Supreme Court’s Dobbs decision. Yet a combination of poor stewardship by Biden and inconsistent media attention, her allies argue, has kept those early days of disaster at the forefront of the popular concept of her. Embracing her prosecutorial background anew, then, could prove to be the reset that Harris has been looking for.

“Prosecutor had a ‘cop’ connotation to it when she initially ran,” the Democratic pollster Celinda Lake told me. “It does not now. It has a connotation of standing up, taking on powerful interests—being strong, being effective—so it’s a very different frame.” She went on: “I just think it’s the right person at the right time with the right profile.” To the extent that the “cop connotation” still exists for some, it might actually work in Harris’s favor: A recent Gallup poll showed that 58 percent of Americans believe the U.S. criminal-justice system is “not tough enough” on crime—a significant change from 2020, when only 41 percent, the poll’s record low, said the same.

For the Harris campaign, this has translated into an opportunity to reach more moderate voters, or at least reclaim those whose support for Harris might have fallen off since the Brett Kavanaugh hearings. “What was considered baggage for her in the last election is now one of her greatest assets going into this one,” Ashley Etienne, the vice president’s former communications director, told me. “As a prosecutor, she can kind of co-opt the Republican message on law and order—not crime, but law and order.”

Which is to say that, much like in 2020, the political environment appears to be dictating Harris’s presentation of her record. Yet unlike in 2020, that environment happens to align with an authentic expression of her worldview. (The Harris campaign did not respond to requests for comment.)

Over the past three weeks, Harris’s friends and advisers have insisted to me that the hard-nosed prosecutor has always been there; people just haven’t cared to pay attention. But there are some problems with this argument. Despite her extensive record on border-security issues as California’s attorney general, Harris often seemed disengaged on even her narrowly defined assignment in the Biden administration’s immigration strategy. In 2021, when Democrats began negotiating criminal-justice-reform legislation, Harris was virtually absent, even though she had been expected to play a central role in those efforts.

When I interviewed David Axelrod, the former senior strategist for Barack Obama, last fall, he wondered why Harris had not already, as vice president, embraced her law-enforcement expertise as a key part of her brand. “She has an opportunity to talk about the crime issue that’s clearly out there, particularly around the urban areas, and talk about it from the standpoint of someone who’s been a prosecutor, an attorney general, and I haven’t seen that much of that,” he said. “Maybe she or they see some risk in that, I don’t know, but I see opportunity.”

Before Election Day, Harris’s law-and-order presentation will need to overcome her party’s larger polling deficit on issues of crime and safety. “By effectively bypassing the primary process in 2024, Harris did not have to ‘play to the base,’ so to speak, this time, but crime is also much more salient these days—and not in Democrats’ favor,” the Republican pollster Kristen Soltis Anderson told me. Trump’s co-campaign manager Chris LaCivita recently told The Bulwark that Republicans are looking to spotlight elements of Harris’s record as a prosecutor, including her 2004 decision not to seek the death penalty against a man who had murdered a San Francisco police officer. (The murderer was sentenced to life in prison.) The Trump campaign and the Republican National Committee have already begun recirculating posts and clips featuring moments from Harris’s 2020 campaign: her support for a Minnesota bail fund amid the George Floyd protests; her vacillation on defunding the police; her raising her hand on the debate stage in support of decriminalizing border crossings.

At the same time, Republicans seem to be ready to paint Harris, when it comes to low-level offenders, as too tough on crime. When I spoke recently with Shermichael Singleton, a Republican strategist, he noted in particular Harris’s aggressive prosecution of marijuana offenses, and her championing of a truancy law as attorney general, which resulted in the incarceration of some parents. (Harris expressed remorse about the truancy law during her 2020 campaign.) As my colleague Tim Alberta has reported, Trump allies plan to use this record to accuse Harris of “over-incarcerating young men of color,” who have been drifting away from the Democratic Party. “Younger Black men, Black men without a college degree, younger Latino men, younger Latino men with or without a college degree—I’m not convinced yet that these numbers move more in her corner,” Singleton said.

For now, the frenzied and unfocused nature of Republicans’ attacks on Harris has allowed her the first word on her candidacy. Over the past few days, many Harris allies have told me they believe that her most urgent task is this: defining her candidacy and her vision for the country before the Trump campaign, Fox News, and the like can fill the void. On that front, Harris seems to have succeeded so far. Her Monday announcement was portrayed across much of the media as a politician introducing herself “on her own terms,” as a New York Times headline put it.

But this narrative, tidy as it might be, implies that, until now, Harris has been operating on something other than her own terms. That’s understandable enough when you’re vice president. Yet at some point, Harris will be forced to reckon with the unanswered questions from her previous campaign for president: why, at the first blush of criticism, she seemed to cede her convictions to the loudest voices in her party—and whether, the next time prosecutors fall out of fashion, Americans should expect her to do the same.