The Last Three Days of Mussolini (1945)

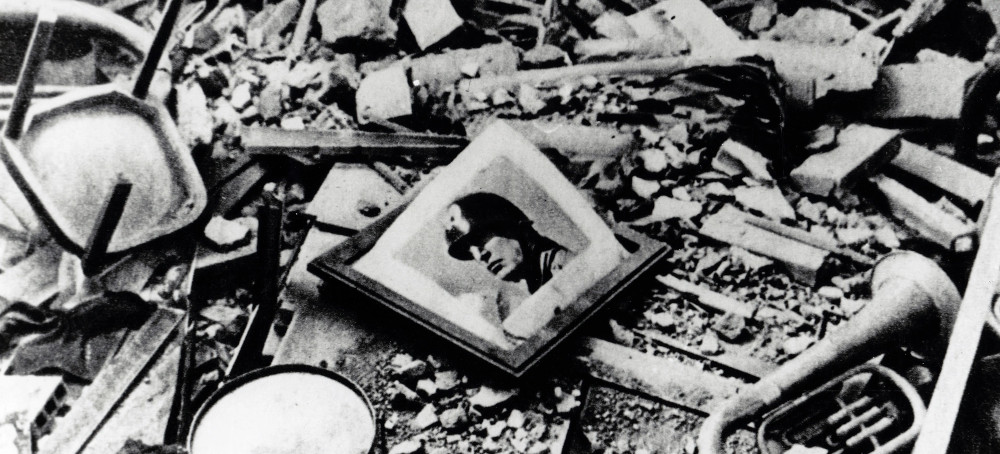

V. Lada-Mocarski The Atlantic Il Duce slumped, first falling to his knees, then leaning sideways against the wall. (photo: Fireshot)

Il Duce slumped, first falling to his knees, then leaning sideways against the wall. (photo: Fireshot)

“Il Duce slumped, first falling to his knees, then leaning sideways against the wall.”

A few hours later, the bodies were taken down by order of the Committee of National Liberation (CLNAI) in Milan; the city had just been liberated from the Axis troops and was not yet occupied by the Allies. The Committee, originally the underground anti-Fascist “Government ” of Northern Italy, was composed of representatives of all the important Italian political parties. It had attempted to prevent the hanging but had failed because it had insufficient police forces at its disposal. During this attempt fire hoses were turned on the crowd, but they also proved ineffective.

The population of Milan had been tyrannized and abused for long months by Mussolini and his regime of oppression and torture. Only a short time before, fifteen members of the Resistance had been executed on this very Piazza, which today bears the name “Place of the Fifteen Martyrs.” It is therefore understandable that the people of Milan were taking their pound of flesh.

V. LADA-MOCARSKI is a vice-president of J. Henry Schroder Banking Corporation, New York. In 1941 he was commissioned in the Army of the United States and saw overseas service for the Office of Strategic Services in the Middle East, Italy, and France. Colonel Mocarski retired from the Army in 1945 but was in Switzerland on a government mission during the last desperate days of Mussolini. On the day of Il Duce’s hanging in Milan, he crossed into Northern Italy. His chronicle is a brilliant example of history as it was written on the spot.

Since the early days of December, 1944, Cardinal Ildefonso Schuster, Archbishop of Milan, had been considering ways and means to prevent the destruction of Milan and other cities in Lombardy as the war approached its final phase and the Axis armies were being driven back towards the Swiss frontier. The Cardinal finally asked Herr Rahn, the German Ambassador with the Neo-Fascist Government, to communicate to Hitler his fervent hope that the German authorities would not find it necessary to carry out any demolition in the city of Milan or any other important point in Lombardy.

In February, Mussolini said in one of his speeches that Lombardy would be defended at all costs. In April, soon after the start of the brilliant offensive by the Allied armies, the situation on the Italian front began to look hopeless for the Axis. The Germans were getting desperate and their emissaries were approaching anyone who was likely to have the ear of the CLNAI, in an effort to arrange for a surrender on terms better than “unconditional.” The Committee invariably replied that it would not negotiate unless the Germans accepted beforehand the principle of unconditional surrender. The Fascist Government finally became aware of these efforts; and beginning on April 22, 1945, several important Fascist officials tried to get in touch with the CLNAI. The Committee’s answer was always the same, with the further qualification that it had at least some confidence in the word of a German soldier, while it had none in that of a Fascist dignitary.

Events were gradually moving to a climax. On April 24 the Committee had one of its clandestine meetings and decided to call a general strike to begin on the following day.

The strike broke out in Milan on April 25 as planned, and the workers started occupying the factories. The Germans’ effort to control it was half-hearted as there were several hundred factories to protect — a task which would have split their garrison into many small units, The Committee then decided to start a military revolt on the following day and to occupy public buildings, utilities, and other strategic points.

On April 25, Cardinal Schuster was told that Mussolini had requested to see him that afternoon because, the intermediary said, Il Duce was willing to sign an unconditional surrender. The Cardinal arranged for the representatives of CLNAI, including General Raffaele Cadorna, Commander-in-Chief of the “Partisans,” the military arm of the Committee, to meet with him and Mussolini. This historic meeting in the Cardinal’s Palace merely showed that Il Duce was not yet ready to surrender unconditionally. After a somewhat heated debate he left the meeting, promising to give a final answer by 8.00 P.M. of that day. Instead, he and the majority of his cabinet fled Milan for an unknown destination.

The Committee of National Liberation then told the Cardinal that it was taking over the government — the Germans had already offered to surrender unconditionally and the Fascist Government was in flight. Milan fell to the liberation movement without organized fighting. The German troops remained in their billets, and there were only separate encounters with a few isolated Fascist troops. The victorious forces of the CLNAI had only a handful of casualties.

2

IT WAS to Como, near the Swiss border, that Mussolini fled after the unsuccessful conference with Cardinal Schuster. With him went a number of his Ministers, among them Marshal Graziani, and other members of his entourage. Altogether there were perhaps fifteen passenger cars and one or two vehicles carrying several German soldiers armed with machine guns. Graziani had his usual escort of one car carrying armed Italian guards.

Mussolini, who was in a foul temper, went to the Prefettura and asked for Signor Celio, Fascist Prefect of Como and head of the Province. Il Duce was incensed at the manner, “unbefitting the Chief of the State,” in which he said he had been treated at the Milan meeting, He asserted it was a low attempt to trick him into accepting something which by its very nature was unacceptable.

At the Prefettura, Mussolini held conferences with several of his Ministers. At one point Celio remained alone with Il Duce and used the opportunity to obtain consent for the creation of a free hospital zone from Como to Lanzo d’Intelvi. This zone, it was hoped, would be spared from fighting. Celio mentioned that the success of this project depended upon “all important political personages” leaving the territory. Il Duce answered that he understood and fully agreed. Shortly afterwards he said he realized that all was lost. When Celio asked what his immediate plans were, Mussolini answered that he was still undecided. Celio suggested that he should ask Switzerland for asylum. Mussolini said he had been notified that Switzerland would not accept him. Celio suggested that another at tempt be made, using the services of the American Consul in Lugano. Il Duce grew angry and said he would have nothing to do with Switzerland. It was close to midnight by that time.

At that moment Francesco Barracu came in and told Mussolini that, despite all the efforts, the “small truck” could not be found. Mussolini flew into a rage and worked himself almost into a fit. He was reproaching Barracu and others that no one had taken the trouble to see to it that this truck with its extremely important documents and the woman who rode in it were safely following him on the trip from Milan. At one point he shouted that it was his tragic destiny for the last twenty-five years to have to attend himself to any important matters — otherwise they would not have been taken care of.

Presently Mussolini called for Graziani, presumably to get his advice regarding the military situation and the plans for the immediate future. Celio had tried beforehand to gain Graziani’s support in convincing Mussolini that he should go to Switzerland. Graziani declined, saying he could not take the responsibility for such a step, as he did not believe Switzerland would accept Il Duce. Graziani was worried about his own situation and said he was at a loss to know what to do.

Shortly before 2.00 A.M. Mussolini sent for Paolo Porta, Federal Commissary of Como, who was later joined by Paolo Zerbino, Minister of the Interior. They remained in the small drawing room for almost an hour and a half, presumably debating the various possible courses of action for the next day. Celio was not present at this conversation, but his impressions were that the trio examined three alternatives. The first was for Mussolini to go to Switzerland. The second was to continue the fight against the Partisans and, perhaps, the Allied troops. It was presumably in anticipation of such a decision that Graziani and Alessandro Pavolini, Secretary of the Fascist Party, were concentrating the Fascist troops near Como and Lecco. There was no way of knowing, however, whether sufficient troops would rally to Mussolini at that stage to make any effective resistance. The third alternative was for Il Duce to hide himself in a safe place until the Allies overran the hide-out. Celio’s interpretation was that the third alternative was decided upon.

Immediately after these discussions Mussolini decided to go to Menaggio, halfway up the western shore of Lake Como. It was possible that Emilio Castelli, the Fascist boss of Menaggio, convinced his chief, Porta, — and through him Mussolini, — that the country around Menaggio was the best place for such a refuge. Mussolini left the Prefettura at Como for Menaggio about 4.00 A.M. on April 26, evidently having had no sleep since leaving Milan. His entourage knew well that it was a question of only a few days before they would lose control of the situation. They were depressed and apprehensive. While there seems to have been no definite plan of how to meet the situation regarding their personal safety, evidently they were told to keep together and to follow Mussolini wherever he went. It was taken for granted that the wives and families would be handled separately from the husbands and that they would not follow them.

Despite the precarious situation, many Ministers and others near Mussolini continued to feel personal attachment to Il Duce and, to a varying degree, were faithful to him. Many of them would have been willing to risk their lives in order to save him; Zerbino, a relatively recent addition to Mussolini’s high council, was particularly devoted and so were Barracu and Gatti, his private secretary.

3

SHORTLY before eleven o’clock a simply dressed woman, who said she was Mussolini’s maid, appeared at the Prefettura in Como and spoke to Celio. She explained that her husband was driving the small truck which should have followed Il Duce’s car. Evidently it was the vehicle which had caused so much excitement the night before. The maid said that the truck had had engine trouble and that her husband had hidden it on a country road only four or five miles from Milan. She added that they were afraid of some untoward happening and asked for help and an escort to get back to the truck and to bring it to Como. Celio had no soldiers under his command and he therefore telephoned to the local Black Shirts requesting that the necessary assistance be given to the woman.

In the meantime, however, the news of the strike and disorders in Milan had reached Como and the Black Shirts were afraid to go there, particularly as they were told that the Partisans were roaming the highways and attacking the Fascists. The woman was stranded in Como and evidently spoke freely of her predicament, mentioning the precious load in the truck. Signora Galli, a patriot who was known to the Provincial Committee of Liberation, heard her story and obtained permission from the Committee to go to take possession of Mussolini’s documents for the Committee. She succeeded in reaching the place where the truck was hidden but found that a unit of Communist Partisans was there and had already grabbed the documents. For some reason these Partisans got the impression that Signora Galli was Claretta Petacci’s mother. They completely undressed her and the poor woman hardly got away with her life.

At Menaggio Mussolini had coffee and slept for a couple of hours in a room on the second floor of the schoolhouse barracks, the headquarters of the Black Shirt Brigade. Shortly after nine o’clock he came downstairs and resumed his interminable conversations with Porta and others. Porta suggested that Mussolini’s motor column, which had increased considerably during the morning with new arrivals from Como, was attracting too much attention and that it should be moved to Grandola, a village a few kilometers from Menaggio on the road to the Swiss border. The convoy moved off by 9.30, leaving no one behind.

One can readily imagine the fatigue, anxiety, and increasing confusion among Mussolini’s entourage. In Como there had not been enough room for everyone at the Prefettura to spend the night halfway comfortably. Most of the meals were eaten standing up or sitting in the cars. Il Duce’s indecision and interminable conversations about what to do next had a depressing effect on everyone. The wanderings of the motor column gave a pitiful picture of the lack of forethought and planning.

About eight o’clock in the evening, without previous advice to Castelli, Mussolini’s convoy returned to Menaggio and went again to the same barracks. Towards midnight Pavolini arrived from Como with two Italian armored cars. Mussolini, Pavolini, and the remaining Ministers again gathered for a long conference which lasted nearly three hours. At 3.00 А.M. Mussolini went to bed, but he slept only one hour. He was up again about 4.00, and at that time Porta gave Castelli the order to prepare the convoy to leave immediately. The chauffeurs were rounded up, and at about 5.00 the motor column headed north.

There was much confusion that morning prior to the convoy’s departure. Mussolini was calm but the nervousness of the others and the atmosphere of panic were upsetting him. Il Duce shook hands with Celio and the prefect saw him get into the passenger car in which he had arrived. Mussolini was wearing the gray-green uniform of the Italian militia with a matching field cap. Before leaving he put on the overcoat of the same organization. It had no insignia of rank except the red stripe of the “Squadrista,” the distinctive insignia of the Fascists who belonged to the movement from its inception.

On April 26 and 27, except for a few armored cars and a handful of soldiers, no Fascist troops reached Menaggio to rally to Mussolini’s side. Several trucks of Mussolini’s German guard must have passed through Menaggio on the way north early in the morning of the 27th prior to Il Duce’s departure. Eyewitness reports made by the inhabitants of Acquaseria (a village on the way to Dongo) indicate that two distinct columns met there shortly before 6.00 A.M. on the 27th. There was a reshuffling of cars at that spot. It is probable that part of Mussolini’s German guard met him there and that Claretta Petacci joined Il Duce at that point. It is also probable that at the same time Mussolini donned a German overcoat and helmet and got into one of the German trucks.

During the night of April 26-27, when Mussolini was in Menaggio, the CLNAI of Bellagio, a town across the lake, telephoned to Castelli saying that if the Fascist forces in Menaggio were willing to surrender, the Committee would arrange for a representative from Como to come to Castelli under the protection of a white flag. Castelli reported this to Porta, who authorized him to enter into negotiations in order to find out what the general situation was in Como.

After Mussolini’s departure Castelli waited for a while; as no one appeared from Como, he and two others went to Cadenabbia to negotiate with the CLNAI there. He reached an agreement for the surrender of his forces, the Partisans consenting that Fascist soldiers should go unmolested, while Castelli and his officials, as well as officers, would place themselves in the hands of the Committee.

The Fascist edifice was crumbling behind Mussolini as he was fleeing north.

4

THE 52nd Assault Brigade “Luigi Clerici" was a part of the Garibaldi Division of the Corpo Volontari della Libertà. During the hard winter spent in the mountains overlooking the western shore of the lake, this “brigade” dwindled to some 15 men. The small size of the unit made it possible for the men to live on the scanty nourishment obtained from friends or sympathizers.

“Pedro” was the commander of the 52nd Brigade, He was a descendant of Florentine nobility and had studied law at the University of Florence. He was just ready to begin to practice when the situation in Italy became impossible and he decided to join the resistance movement. He was in his early twenties and physically not very strong, but he was determined to bring about better days for his country. “Bill,” his right-hand man and subsequently the Political Commissary of the 52nd Brigade, was a young man of simple background. Both men were “real” Partisans as distinguished from “eleventhhour” Partisans — an appellation given to those who actively joined the resistance movement on or after April 26, the day on which the real Partisans came out of hiding and openly attacked the Germans and the Fascists.

Towards the end of April, Pedro’s unit was running short of supplies and the Partisans had not had a smoke for nearly two weeks. Finally they could stand it no longer, and on the morning of April 26, Pedro and 14 or 15 of his men came down to Domaso, where there was no Fascist garrison, and bought some tobacco. While there they heard a radio broadcast saying that the Allies were advancing rapidly from the southeast and that there were units near Brescia. Pedro decided to remain in Domaso, to erect a road block, and to intercept any Fascist or German convoy. No such convoy appeared during the day, but they received intelligence that there were some German troops in the barracks at Gravedona.

Bill and several other Partisans went to Gravedona, deposited their arms before entering the barracks, and convinced the Germans that they should lay down their arms. In return the Partisans undertook to allow the Germans free passage within their territory.

The way south to Menaggio was now clear and the Partisans went on to Dongo and Musso, gaining adherents on the way. They erected another road block at the northern approach to Musso, a few hundred yards south of the small bridge over the Valorba River.

Early on the morning of April 27, Pedro and his men were at Musso at this northern road block. The block consisted of large rocks and barbed-wire entanglements placed across the main road running on the western shore of the lake. This road was the only avenue of retreat for any German or Fascist formation that might be making its way from Menaggio to the Swiss frontier at Villa di Chiavenna or to Austria.

On one side of the block were the waters of the lake; on the other, steep hills rose almost perpendicularly. Several Partisans were guarding the road block and the rest were scattered around with a few sentries placed in the hills overlooking the road. The Partisans were armed with rifles, hand grenades, and a few submachine guns. Their fire-power, however, was small.

About 6.30 A.M. the sentries in the hills signaled the approach of a large convoy. Shortly afterwards, the convoy arrived near the road block and stopped. An Italian armored car, which led the column, opened machine-gun fire in the direction of the block. The Partisans answered and the fire continued for three or four minutes. Neither the convoy nor the Partisans suffered any casualties, but a workman farther along the road was killed.

Suddenly the convoy hoisted a white flag and the firing ceased. Several German soldiers in the column left their trucks and asked for the Partisan commander. Pedro and Bill, who were near the road, spoke to a German Luftwaffe lieutenant who seemed to be in command of the convoy. The lieutenant proposed that the convoy should be allowed to proceed without molestation; and in return for this permission the Germans would refrain from making any reprisals.

Pedro countered by saying that the Germans should first give up their arms and any Italians they might have with them. The German officer said he could not surrender the arms because they were bound for Germany to fight the Allies; he also said that he had no Italians with him. Pedro, since his men were woefully outnumbered, — there were at least 200 Germans with a far superior fire-power, including an armored car carrying a cannon, — was dragging out the negotiations, having in the meantime sent for reinforcements from other Partisan units farther north.

Finally the negotiations came to a standstill. Then Pedro had a happy thought: to tell the German officer that he had no authority to accept such terms and that they would have to go to Morbegno, some 20 miles ahead, to the headquarters of the Garibaldi Division. The German readily consented and Pedro departed with him, leaving Bill in charge. The attitude of the German lieutenant is difficult to understand unless he was misled as to the number of Partisans who were facing him, or unless his men were not prepared to fight.

On the way, Pedro pointed out small bridges and other obstacles, telling the Germans that they were all mined and ready to be blown up if the Germans attempted to force their passage. This, of course, was a mere invention on Pedro’s part.

In the meantime additional Partisans were arriving, so that by the time Pedro and the German lieutenant returned to Musso there were almost 100 armed men to oppose the Germans. Nevertheless, the Germans were still stronger, as to both the number of their soldiers and their armament; in addition to the armored car there were twenty-nine trucks with soldiers and eight passenger cars.

While Pedro and the German lieutenant were away, the Germans in the convoy left the trucks, spoke with the population, and smoked.

Pedro knew that there were no Partisans between Dubino, a village on the way to Morbegno, and Morbegno. He therefore left the German officer in Dubino and went on alone to where “Nicola,” the commander of tlie Garibaldi Division, had his headquarters. Nicola did not have much in the way of additional reinforcements to give Pedro and left it to him to obtain the best possible terms, disarming the Germans if possible.

Pedro returned to Dubino and told the German officer that he was authorized to allow the Germans to keep their arms provided they gave up all the Italians in the convoy. The Germans were to submit their vehicles to a search at Dongo, in order that this condition might be carried out.

Pedro realized that he did not have enough men to force the Germans to disarm at Dongo. Furthermore the terrain there was not so advantageous as farther up the lake at Ponte del Passo, which the convoy would have to traverse on the way to Chiavenna. The Partisans hoped that they could muster enough people to disarm the Germans there.

The German lieutenant said that he would have to consult his colleagues. Pedro and the German returned to Musso early in the afternoon. After speaking with others in the convoy, the German lieutenant informed Pedro that he was ready to accept his conditions but that he could not guarantee the behavior of the Italian armored car.

5

THE German convoy arrived at Dongo about 3.00 P..M. In accordance with Commander Pedro’s instructions, Bill arranged for the search of all the vehicles, distributing this job among several Partisans. The Germans, numbering perhaps 200 men, still had their arms. One could expect a group of this size and fire-power to put up considerable resistance and to impose its will, at least temporarily, on the Partisans, whose armament was much inferior and who, it was reasonable to suppose, were anxious to avoid an out-and-out fight. But the Germans did not want to fight for their Fascist allies, however important they might be.

There was much excitement in Dongo while the convoy was being searched. The Partisans soon found an Italian Air Corps officer who was wearing a German uniform. They also found a man, two women, and two small children who claimed to be Spanish and who produced Spanish papers showing that they were consular officials proceeding to Switzerland. The man spoke for all of them. In the confusion he produced three passports, one covering himself, another covering his wife, and the third covering them both and issued in the name of Don Juan Munez y Castillo. There was also another passport for the second woman in the car.

These documents had obviously been hurriedly fabricated; one of them gave 1912 as the date of the man’s birth, the other had 1914. Instead of the usual pressed seal it had a rubber stamp. The children were chattering in Italian and asked who the man was who was interrogating them. When told he was a Partisan, they said that the Partisans were stupid and bad.

The Spaniards were told that only the Germans could continue the trip and that they would have to remain in Dongo. Someone from the Partisans addressed the pseudo-Spanish consul in Spanish and ascertained that he did not speak the language. The “consul” and his wife were allowed to move into the local hotel, pending the further disposition of their case. The other woman, who later on proved to be Claretta Petacei, Mussolini’s mistress, was taken to the Municipal Building.

Bill had just finished searching the second German truck when one of the eleventh-hour Partisans ran up to him saying that he had discovered a very suspicious-looking German in the truck farther down the column. Bill and the Partisan went immediately to this truck and saw a man crouching on the floor with his back against the railing. He wore a German overcoat with raised collar and helmet.

Standing on the ground, Bill reached up and touched the suspect’s back, calling out to him. “Camerata.” The man did not move; Bill then addressed him as “Eccellenza”; still there was no reaction from the man. “Cavaliere Benito Mussolini,” cried Bill, and the man’s back shook. Bill jumped into the truck accompanied by the Partisan.

The German soldiers who were in the truck when the first search was conducted had got out of the vehicle and were standing around it. One of them said that there was a drunken “Kamerad” lying in the truck and that he should not be bothered. Bill answered that he would see for himself and approached the man he had just spoken to, who was surrounded by a pile of blankets and was still crouching on the floor, holding a submachine gun between his knees. Bill could not see his features, and he unceremoniously removed the German helmet, revealing the well-known bald head of Il Duce.

Realizing that he was recognized, Mussolini stood up and said, “I am not resisting.” Bill took the submachine gun from him and handed it to the Partisan. He then took Mussolini by his left arm while the Partisan took his right arm and the trio were ready to step out of the truck. Bill was expecting the German soldiers to open fire and he thought that his last minute had come. It was not reasonable to assume that the Germans would give up Mussolini so easily. Il Duce told him later that the Germans had been instructed to shoot the minute he was discovered. However, no one lifted a finger in Il Duce’s defense — instead the Germans obligingly lowered the folding steps at the back of the truck and Mussolini with his captors stepped to the ground.

Mussolini was obviously dejected but tried to put up a bold front. On the way to the near-by Municipal Building, Bill told Il Duce that he would guarantee his personal safety as long as he was in his custody. Mussolini gave a sigh of relief. A Partisan led the way while Bill followed Il Duce with a drawn revolver. He noticed that Mussolini had an automatic pistol hanging from his belt and he took it away from him.

Il Duce was placed in a big room, on the ground floor of the Municipal Building, on the left-hand side of the main entrance. Upon entering this room, he threw off the German overcoat and exclaimed, “Enough of all things German! They have betrayed me for the second time.” Whether this remark referred to the German escort’s unwillingness to fight it out with the Partisans in order to protect him or whether he had something else in mind is not clear.

A number of armed Partisans were placed in the room to guard Mussolini. He remarked that his captors need not worry as he would not run away. Bill remained with Il Duce for a while, plying him with questions.

“Where is your son Vittorio?”

“I don’t know.”

“Where is Graziani?”

“I am not sure, but I believe he is in Como; he betrayed me at the last moment and refused to come along.”

“Why were you in a truck when some of your Ministers were riding in an armored car?”

Mussolini muttered something again about being betrayed.

6

ON THE following day when the arrest of Mussolini and his Ministers became widely known, stories of the circumstances surrounding his capture were circulated in the countryside near-by and in Como and Milan. Almost all of these were untruthful. The newspaper reports were also far from authentic — even the locality in which he was captured was given incorrectly. The few eyewitnesses of the various episodes remained on the spot and there was a general reticence on their part to relate the exact circumstances and the role which they themselves had played.

One of the widely accepted but incorrect statements was that Mussolini was kicked and generally maltreated when first discovered in the German convoy. A thorough investigation in Musso and Dongo, including frank and friendly conversations with several participants in the capture and with other eyewitnesses, revealed the fact that the behavior of the Partisans and of the local population was restrained and that neither Mussolini nor the other prisoners were exposed to any maltreatment.

As a matter of fact, the civilian population had almost no direct contact with the prisoners during the little more than twenty-four hours which elapsed from the time of the capture to the execution. The Partisans were a disciplined formation led by Pedro, a man of excellent background, who was obeyed without question by his men. Furthermore it is probable that the instinctive fear of the Fascist authorities with which the entire population was imbued was still strong enough in the minds of the “patriots” to induce in itself sufficient restraint towards their prisoners. The fact that their newly won supremacy was but a few hours old and might be challenged at any moment by the Fascist troops, such as the various Black Shirt divisions stationed only a few miles away, must have exercised considerable influence on their minds.

The telephone communications between Dongo and Como were interrupted by the Partisans. The Partisan road blocks between Gravedona and Menaggio stopped practically all traffic, as the Partisans were taking no chances of letting any traveler pass from the territory under their control into the surroundings of Como, which were still infested with Fascist formations. It was therefore by a mere chance that the authoritative news of the capture of Mussolini reached the CLNAI in Milan. It happened in the following way.

“Carlo,” commander of one of the small Partisan detachments, had his headquarters at Gera Lario, a village at the northern end of Lake Como. When he heard that a large German-Italian convoy in which Mussolini was traveling had been stopped by the Partisans at Dongo, several miles away, he decided to go there.

To satisfy himself that Mussolini had really been captured, he went to the Municipal Building and saw Il Duce with his own eyes. Carlo returned to Gera Lario and went to the offices of the Idro Elettrica Comacina, where there was a private line to the company’s headquarters in Milan. At 5.30 P.M. he telephoned Milan and spoke to an engineer of the company, instructing him to communicate to the CLNAI that Mussolini was really captured. An hour later an answer came over the same line with instructions to guard Mussolini carefully, to take every precaution that he should not escape, and in the meantime not to harm him in any way. Carlo communicated these instructions to Commander Pedro and to Bill.

7

EVEN before receiving these instructions, Pedro decided that the location of Dongo on the main road, with its relative proximity to Como and Menaggio, might present an opportunity for a Fascist coup to liberate Mussolini. He therefore decided to move Il Duce to Germasino, a small village in the hills near-by.

The approach to Germasino is not easy. The road is narrow and has a number of hairpin curves. At a height of about 1900 feet are the barracks of the Guardia di Finanza, a detachment of which was charged with the surveillance of the near-by ItalianSwiss frontier. The Guardia di Finanza as a body had been very sympathetic to the Partisans in their strife against the Fascists. The Germasino detachment lent them arms on several occasions and during the cold winter months they often allowed Pedro’s Partisans to spend the night in their barracks. Many members ol this front ier unit openly went over to the Partisans and served in the ranks of the Garibaldi Division long before the final overthrow of the Fascist regime. The Partisans could therefore count on the discretion and assistance of this particular unit when they were looking for a place to keep Mussolini.

Between 6.30 and 7.00 P.M. Pedro took Mussolini and Porta from the place of their detention at Dongo and drove them to Germasino, accompanied by a brigadier of the Guardia di Finanza and a fervent patriot. The small car in which they climbed the steep road was followed by a somewhat larger car with eight Partisans as guards; seven more were following on foot and arrived at the barracks in due course.

Mussolini was taken into the office on the second floor of the main building, belonging to Antonio Spadea, local commander oh the Guardia di Finanza. While still on the stairs, Pedro asked Mussolini whether he had any special requests to make. Upon entering Spadea’s office, Mussolini took Pedro aside and, in a hushed voice, asked the Partisan chief to do him a great favor. He asked Pedro to tell the lady who was traveling with the Spanish consul and his wife that he was well and that everything seemed to be in order. Pedro asked who the lady was and Mussolini answered that she was a good friend of his. “But who is she?” insisted Pedro.

La Petacci,” said Mussolini, lowering his voice still further.

Leaving fifteen Partisan guards, mostly eleventhhour recruits, to guard Il Duce, Pedro went back to Dongo. Mussolini must have arrived at Germasino shortly after 7.00 P.M., and Pedro left for Dongo within half an hour.

On his return to the Municipal Building at Dongo, Pedro spoke alone to Claretta Petacci and told her of Mussolini’s message. Petacci pretended at first not to understand, and expressed surprise that Il Duce should be sending any messages to her. Pedro abruptly said that Mussolini had confided in him and that she might do likewise. Petacci and Pedro then spoke frankly with each other for over an hour. She told him a good deal about her life and her relations with Il Duce. During this recital she cried several times. Evidently she made a decided impression on the young Partisan chief. Before leaving her, he asked her in turn whether she had any requests to make.

Petacci answered that she did not know what the Partisans were planning to do with her, but that she supposed they would release her before long. It was her desire however, she said, to stay with Il Duce even if it meant death, and she begged Pedro to let her join Mussolini wherever he was. Pedro said that he did not see how this could be done at that moment, but he promised to do it later if it was at all possible.

Shortly after one o’clock that night (April 28) Pedro returned to Germasino. On arriving at the barracks, he learned that Mussolini had been placed in a cell on the third floor. Il Duce was lying in bed but was not asleep. Pedro told him that he regretted disturbing him, but he had come to move him to another place. Il Duce said he had expected such a move, as he did not think he would be left in Germasino long. He dressed and went to the office on the floor below. Pedro told him that he would have to have his head bandaged in order to prevent possible recognition on the way.

Pedro was planning to take Mussolini all the way to Como and he was afraid that some Partisan road block might mistake him for a Fascist liberating Mussolini. There was still a great deal of confusion in the countryside and little coördination between the various Partisan units covering different sectors of the main road to Como. Pedro and Mussolini descended the steep hill road from Germasino to Dongo. Not far from the latter, in a prearranged spot, they met the car with Claretta Petacci, escorted by Captain “Neri,” chief of Pedro’s staff, and “Pietro,” another Partisan.

In Moltrasio, a few kilometers from Como, Pedro heard a good deal of shooting. It was continuous and strong, indicating a fairly large number of fighters. Pedro and Neri thought that this might be an attempt by some Fascist formations to force their way to Dongo to liberate Mussolini. They decided that it would not be safe to proceed farther and they went into consultation as to where Mussolini and Petacci should be taken. Neri described a house in Bonzanigo di Mezzegra, a remote settlement in the hills above Azzano. He himself had spent many a night in this house, hiding from Fascist pursuit, and he knew the owners, simple country folk, very well, He was absolutely sure of their discretion and loyalty. Everyone agreed that this was a good place and both cars retraced their way to Azzano, some 15 or 20 kilometers distant. Mussolini and Petacci had passed through Azzano on their way to Musso and Dongo, in the German convoy.

Both on their way to Como and on the return trip, the cars were stopped by the Partisans several times. Pedro and Neri said that they were transporting some wounded Partisans and they were allowed to proceed.

8

AT Azzano, at the intersection of the main road with the country road leading uphill to Bonzanigo, the cars stopped and the passengers all got out. Pedro, Neri, and Pietro escorted Mussolini and Petacci to the house selected as the next abode for them. The party took a short cut, avoiding the main country road. It was uphill going and it was raining. Petacci was very tired, so the party proceeded slowly, arriving at the house of Giacomo de Maria between 2.00 and 3.00 A.M.

The master of the house was awakened. He readily offered his hospitality to the wounded German couple — that is how Mussolini and Petacci were introduced to him. On entering the dwelling, Mussolini greeted his hosts with “Buona sera.”

The humble mistress of the house asked for a little time to tidy up the room on the third floor, in which their two sons were sleeping. They were awakened and sent into the mountains to a hut belonging to the family. Pedro asked the woman to use new and clean linen, if possible, and to put the best there was at the disposal of the couple, He added that they might remain for two or three days. The good woman did as she was told, never imagining who her guests were. When the wounded man was offered coffee in the kitchen, he abruptly said he didn’t want it. He generally had a commanding attitude, although he looked old and tired. Shortly afterwards the couple were taken upstairs.

Their room had one entrance door and a window in the same wall. A double bed was placed parallel to this wall. At the head of the bed hung three cheap religious pictures. Against the opposite wall stood a small iron washstand, while on the wall facing the window hung a discolored photograph of a cousin of the mistress of the house, killed during World War I. Wooden chairs completed the furnishings of this small whitewashed room.

The couple brought no suitcases or other belongings, except that the woman had a foulard kerchief with a pair of shoes tied in it, and a blue fur-lined cap that tied under the chin. The couple also had with them a gray Italian Army blanket which was placed on the bed when Petacci said that she was cold.

Mussolini hardly spoke at all, but did ask for two pillows. Petacci asked for a comb and various other things. In the room upstairs, Mussolini took off his bandages. The peasant owner of the house was in the room at that moment and recognized him, but kept still and said nothing to his wife. The Partisan who was mounting guard in the small hall adjoining the room locked the door from the outside, and two Partisans were left in the house to take turns in guarding Mussolini. Pedro, Neri, Pietro, and the rest departed.

The couple slept until almost midday (Saturday, April 28). Upon arising, Petacci asked for polenta, a kind of corn meal, and for some milk. Two portions of this were brought up, together with a plate of salami and rationed bread. Petacci ate with appetite; Mussolini took only two slices of salami and some bread. He did not drink the milk, just as the evening before he had refused coffee, and drank some water instead. Was he afraid of being poisoned?

Mussolini looked rested and much younger after the night’s sleep. He washed but didn’t shave. He spoke very little and looked sad. To anything that was said to him, he invariably answered “Bene, bene.”

In the meantime, the inhabitants of the village were much excited because the rumor had spread that in the afternoon of the previous day Mussolini had passed on the main road below. The mistress of the house remained inside the entire morning, but her husband went out, working around the house, and even walked in the village. He never said a word about his guests, whose presence thus remained unknown until the moment of their departure. Someone in the house mentioned the fact that the American troops had reached Como. Opening his door, Mussolini asked whether this was true, and received an affirmative reply. He was visibly moved by the news.

About four o’clock, a “Colonel Valerio” and Pietro arrived at the house. Valerio was escorted to the room upstairs by Giacomo, who remained outside. After knocking, Valerio entered the room. From behind the closed door, Giacomo distinctly heard him urging Mussolini and Petacci to leave with him at once. Valerio kept repeating that there was no time to lose. In a few minutes, Il Duce and Petacci left the house. Petacci was leaning on Mussolini’s arm, pale and crying. Mussolini was making a show of boldness and was pulling her with him.

Colonel Valerio, representing the CLNAI and General Cadorna, Commander-in-Chief of the Corpo Volontari della Liberià, had arrived in Dongo about one o’clock on Saturday, April 28. He identified himself to Pedro and produced a document stating that he belonged to the Milan Partisan headquarters and was charged with an important mission in the execution of which all Partisan formations were instructed to assist him. He told Pedro that his mission was to execute Mussolini, Petacci, and various Fascist dignitaries. After some hesitation Pedro accepted Valerio as his superior officer, whom he was to assist in carrying out his mission.

9

VALERIO had neither specific written orders nor a list of persons to be executed, a fact which is not surprising since there were no reliable communications between Dongo and Milan and since the Central Committee in Milan did not even know exactly who were in the Partisans’ custody. Valerio therefore asked Pedro for a list of persons and the places of their detention. Such a list, with a grand total of 49 captured at Musso and Dongo, was shown him. It included not only the Ministers and dignitaries but also chauffeurs and others. In addition to Mussolini and Claretta Petacci, Valerio selected sixteen others: Alessandro Pavolini, Francesco Barracu, Paolo Porta, Nicola Bombacci, Vito Casalnuovo, Ernesto Daquanno, Pietro Callistri, Goffredo Coppola, Augusto Liverani, Luigi Gatti, Ruggero Romano, Mario Nudi, Fernando Mezzasoma, Paolo Zerbino, Uttinperger, and Marcello Petacci.

It was only upon the arrival of Valerio at Dongo that the “Spaniard” who was in the car with Claretta was identified as her brother Marcello. Valerio arrived believing that the person in question was Vittorio Mussolini. As this “Spaniard” continued to deny that he was Vittorio, Colonel Valerio gave orders to Bill to have him taken to the local cemetery and be given three minutes to divulge his identity, failing which he would be shot at once.

Marcello Petacci then told who he was and, when asked for proof, referred to his real documents concealed in the room of the hotel where he had spent the night. The documents were duly found. His name was then added to those who were to be shot.

On the pretext that he came to “liberate” them, Valerio took Mussolini and Petacci from the house at Bonzanigo about four o’clock. If Duce was wearing an iron-gray overcoat with his collar pulled up and a cap pulled down over his eyes. Claretta Petacci was wearing a simple gray suit and a silk kerchief on her head. Both wore black riding boots. The escort consisted of Colonel Valerio, the Partisan Pietro, and the two Partisans who stood guard during the night. Il Duce and his mistress first walked up the hill on Via del Reale and then took Via Mainoni l’Intignato. Halfway down that street, Mussolini suddenly looked as if he were going to collapse, but he immediately regained his composure. The few people who were on the street at that time were ordered to go away, but there were several persons still tarrying who saw the procession.

Via Mainoni l’Intignato leads to a small piazza in which there is a long stone basin, with constantly running water, the wash place of the village. At the eastern end of the piazza there is an archway which marks the beginning of Via 24 Maggio, which winds down to Azzano, passing through Giulino. Waiting at the entrance to the archway was Valerio’s car. The party stopped there. It was rather dark under the archway and the place would have been fitting for an execution. However, the presence of two persons near-by, and of two others near the wash basin a short distance away, made this site impracticable.

They got into the car and were driven along Via 24 Maggio, reaching the small settlement of Giulino di Mezzegra and stopping in front of a gate bearing the number 14. At this point, the road turns slightly and nothing on it can be seen from the north. A sharp curve preceding this point in the road conceals the view from the south. Looking down and to the left from the gate, towards the lake, one can see the trees of Tremezzo. Beyond the lake is the country around Bellaggio.

Behind the gate, a short way up, stands the Villa Belmonte, to which gate 14 is the entrance. Among these beautiful surroundings, Valerio made Mussolini and Petacci leave the car, pretending that he heard a suspicious noise which he wanted to investigate. Startled and dumfounded, they heard their death sentence suddenly read to them by the man from Milan. Mussolini was then ordered to move a few paces away towards the stone wall at the northern end of the gate. Almost simultaneously Colonel Valerio’s gun rang out. He was standing somewhat to the side of Mussolini, and his five shots caught Il Duce obliquely in the chest, bringing him to his knees.

Il Duce slumped, first falling to his knees, then leaning sideways against the wall.

It was then Petacci’s turn — she lifted her arms in a desperate gesture, received several bullets in the chest, and fell by the side of her lover, their bodies touching. The time of the execution must have been between 4.15 and 4.30 P.M.

Valerio then returned to Dongo, where he arrived shortly before 5.00 P.M. In the meantime, the prisoners held at Germasino were brought to Dongo. Upon Valerio’s return the preparations for the execution of the sixteen persons previously selected were promptly made.

Padre Acursio Ferrari, a priest from a neighboring monastery, asked Colonel Valerio for permission to give the last rites of the Church to anyone who might wish them. Ministers Romano and Liverani had previously sent word that they would like to receive religious comfort from a priest. Colonel Valerio said that the Padre could have three minutes for that purpose. When the monk remonstrated that this was hardly sufficient time for so many people, Valerio replied that military exigencies did not allow any extension.

After receiving absolution “en masse” the prisoners were told to turn around and face the lake. It became obvious that they were to be shot in the back. Barracu then pleaded for the right to face the firing squad because of two gold medals, the highest Italian awards for bravery, he had earned during World War I. Valerio flatly refused this request. The prisoners shouted three times, “Evviva l’Italia!” and the platoon of execution, composed of Valerio’s men from Milan augmented by several local Partisans, opened fire. It was exactly 5.17 P.M. Several prisoners were not killed by the first volley. A few struggled on the ground; one tried to get up. The platoon of execution continued to fire until there was no sign of life. It was all over.

Marcello Petacci was not executed with the rest, although Valerio included him among those to be shot. When he was led out from a separate cell, in which he had been confined, the other prisoners, already assembled in the Piazza, shouted that they would not have him executed with them because they did not want to have the blood of the villain and the spy mix with their own. Valerio yielded to the determined and angry shouting of the prisoners and Petacci was led away.

Immediately thereafter, he was led out again and conducted to the scene of execution. He broke down completely, cried and begged for mercy. Within sight of the corpses of those who had just died, he made a desperate attempt to escape by jumping into the lake. The Partisans opened fire from the shore and he was killed in the water. The body was later retrieved and added to the rest.

A truck took all the bodies from Dongo to Azzano. Mussolini and Petacci were brought down to the same spot from Giulino di Mezzegra. Neither of them lost any blood at the place of execution, but when Mussolini’s body was being placed in a truck at Azzano, it suddenly started bleeding profusely and a large puddle formed on the pavement. The truck with all the bodies then started for Milan.