The Enemies List: What Was It Like to Be on Richard Nixon’s?

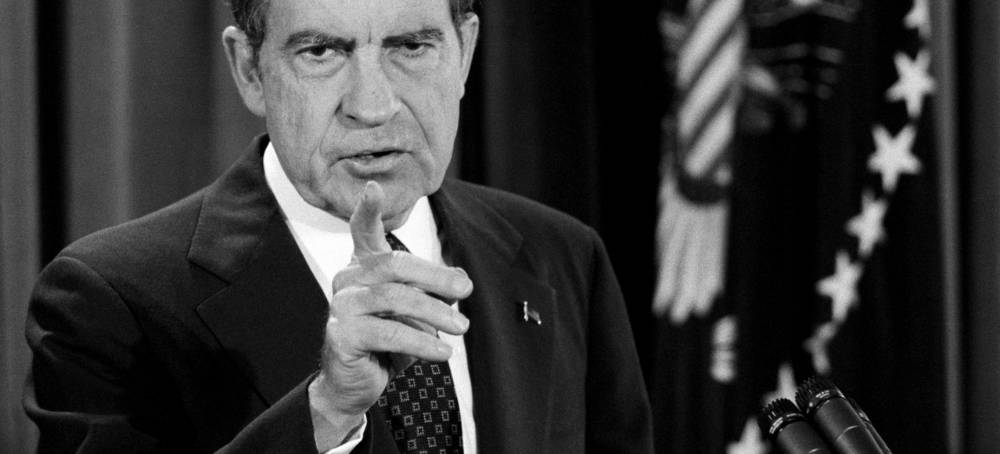

James Robenalt Vanity Fair President Richard Nixon during televised news conference in the East Room of the White House, March 6, 1974. (photo: Getty)

President Richard Nixon during televised news conference in the East Room of the White House, March 6, 1974. (photo: Getty)

In the early ’70s, making it onto the president’s roster was considered “a badge of honor.”

So it seems like an appropriate moment to look back at Nixon’s time in office and ask: What was it like to be on his enemies list?

I have a unique perspective to add here because I have traveled, off and on, for more than a decade with Nixon’s former White House counsel, John Dean. Together we presented a legal ethics course to lawyers, framing Dean’s experience during the Watergate scandal as our teachable moment. Dean is, in fact, the insider who revealed the existence of Nixon’s enemies list (actually lists) during his testimony before the Senate Watergate Committee in June 1973, two months after he broke with the White House and testified against the administration as the panel’s star witness.

Dean’s disclosures on national television caused a media firestorm. As it turned out, a short list of 20 names had been developed by an aide who worked for Charles Colson, Nixon’s special counsel and notorious hatchet man. That list consisted of people who were not to be invited to the White House for any events, under any circumstances, and were otherwise marked for future harassment. Far longer lists were compiled, in haphazard fashion–an inventory of a whole raft of “political opponents.” Famously, when the short list was handed over to the press during the Watergate hearings, the decorated CBS News correspondent Daniel Schorr was breathlessly reading from the list, live on the air, when he unexpectedly came upon his own name—number 17 on the list. Later, he admitted, “I felt as if I was going to gulp and collapse.”

Little was done with either the short list or the longer compilation during Nixon’s first term. A congressional investigation of the IRS in late 1973 concluded that there was “no evidence that those on the list were harassed by the tax agency.” But as Nixon contemplated what he might do in a second term, he began to discuss with his top aides his intent to be more aggressive with his enemies. (The conversations were secretly recorded on a clandestine White House taping system.) Referring to the FBI and the Justice Department, Nixon warned that the administration had not “used the power in the first four years,” but that “things are going to change now… They are asking for it and they are going to get it.”

It would be his revenge tour.

Celebrities like Jane Fonda, Paul Newman, and Barbra Streisand regarded their inclusion as a “badge of honor.”

At the time—in September 1972—Nixon led the Democratic nominee, South Dakota senator George McGovern, in the polls by 20 or 30 points. Nixon believed (correctly) that he would likely coast to a second term, even though the Watergate break-in had occurred the previous June, and Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein of The Washington Post were doing all they could to keep evidence about the administration’s political criminality in the public eye. But as Election Day approached, no one cared about Watergate. Voters were more concerned with bringing the Vietnam War to an end, though most rejected the immediate withdrawal that McGovern advocated. Nixon promised “peace with honor” and won in a historic landslide, taking every state but Massachusetts, and the District of Columbia. The House and the Senate, however, remained in Democratic control (Joe Biden was elected to the Senate that November)—and Nixon’s political fortunes were soon hanging in the balance.

By the time John Dean revealed the enemies list in the summer of 1973, Nixon’s favorability index was starting to slip. CBS newsman Schorr’s reaction to the existence of the list—breaking out in a cold sweat—was not the common response, mainly because Nixon was already wounded politically. Most saw the list as something of a joke. As Dean wrote in his best-selling confessional, Blind Ambition, “It became an instant status symbol to be on it.”

Celebrities like Jane Fonda, Paul Newman, Barbra Streisand, Tony Randall, and Carol Channing all spoke of inclusion on the enemies list as a “badge of honor” or one of their “greatest accomplishments.”

“I was on Nixon’s enemies list, which I was very proud to be, and I still am very proud to be,” Streisand told Bill Maher in 2017. Dean himself confided to me this week: “In all the years since revealing Nixon’s enemies list, and encountering many who were on it, I have never had anyone tell me they weren’t proud to be on the list.”

Gonzo journalist and author Hunter S. Thompson expressed disappointment in not having been included on the list, writing in his 1979 book, The Great Shark Hunt: Strange Tales from a Strange Time, "I would almost have preferred a vindictive tax audit to that kind of crippling exclusion."

John Dean: “I have never had anyone tell me they weren’t proud to be on the list.”

Over time, the lists became undisciplined. Nixon’s aides kept a rambling compilation of hundreds of names that included business and religious leaders, the Black Panthers, the Berrigan Brothers (Catholic priests who mobilized protests against the war), journalists like syndicated columnist Jack Anderson, Max Lerner of the New York Post, James Reston of The Washington Post, and elected officials, including Senators Ted Kennedy and Walter Mondale. This master list was so sprawling that it sometimes included people who had no particular beef with the Nixon administration. The star quarterback of the New York Jets, Joe Namath, for instance, randomly made it onto Nixon’s registry, but he was described, mistakenly, as being a member of the New York Giants.

In the ensuing decades, the concept of an enemies list would take on a life of its own, permeating popular culture. During Bill Clinton’s presidency, P.J. O’Rourke, the right-of-center provocateur, compiled “The Enemies List” for The American Spectator. On The Simpsons, Homer would keep a “revenge list” of particularly irksome people and topics (“GRANDPA… GRAVITY…”). More recently, political commentator Rick Wilson, the “never Trump” Republican who cofounded The Lincoln Project, has been hosting a podcast called—what else?—The Enemies List.

In 2012, when John Dean, Jill Wine-Banks (the former Justice Department and Watergate prosecutor), and I presented a legal ethics program for law students at the University of Minnesota Law School, Walter Mondale, the longtime Minnesota senator and Jimmy Carter’s vice president, joined us. (The law school building, after all, is named Walter F. Mondale Hall.) He spoke discerningly about Richard Nixon and what led him to obsess about enemies.

“He did many good things while he was president,” Mondale conceded. “He was very impressive in international affairs—he helped overcome the gap between the United States and China. In civil rights fights that we were involved in, in many of them he was on our side. And many of the judges he appointed to the bench were, you’d say, moderates—sensible people trying to make things work.”

But Nixon had a fatal flaw. “I believe he was paranoid,” Mondale said. “I believe he had a deep, dark side to him that often overwhelmed him. When someone would do something or say something he didn’t like, he wasn’t able, as you should be if you’re going to be in politics, to handle it and move on—to make your arguments, to be heard, to have a campaign, and so on—a civil way of resolving or accepting it. Deep down he had within him some sort of force that required him to dwell on it, to plan on some way of removing this source of criticism.”

If that sounds familiar, it should. Donald Trump, who fashioned so much of his political worldview from Nixon’s time, shares Nixon’s temperament. He is incredibly press-conscious and thin-skinned, and he has said that in his second term he may retaliate against members of the media, politicians, and those who prosecuted (he says persecuted) him. The question is: How serious will these efforts be?

“Things are going to change now,” Richard Nixon said. His second term would be his revenge tour.

Unlike Nixon, Trump has declared his intentions in public, so no one can say they have been misled. In Nixon’s second term, the opposition party held both houses of Congress; Trump does not face that hurdle. And the current political climate, different from the one during Nixon’s era, seems to bolster Trump. He already commands a compliant arm of the media (from cable news channels to X to like-minded social media influencers and podcasters) and even has his own online platform, Truth Social. In this perilous, corrosive environment, the American public—or at least large numbers of it--may very well abide political prosecutions against Trump’s purported “enemies.”

As I have recently written in Vanity Fair, much will depend on those who occupy top posts at the Justice Department and key legal slots in the administration. Trump’s initial selections seem to signal that he values loyalty over the rule of law. Then there is the conservative-dominated Supreme Court, which, in holding that a president is “entitled to absolute immunity from criminal prosecution” for his official acts, has indicated that it takes a breathless view of executive power; far be it for them to step in to rein in Trump prosecutions.

It is, in a word, a dangerous time.

Fifty years ago, Nixon’s enemies list sparked little fear of actual revenge. Even Mondale found humor in it when he spoke in 2012—a time when Trump was nowhere on the political radar. Mondale recalled how he and fellow Minnesota senator Hubert Humphrey (who had been Lyndon Johnson’s vice president and had run against Nixon in 1968) were in the Senate cloakroom during the Watergate hearings as names from Nixon’s enemy lists were being read on TV. “I ended up number three on Nixon’s enemies list,” Mondale recalled, “and Humphrey wasn’t on the list at all. And there was a long, embarrassed moment there, and I said, ‘Hubert, I never trusted you.’”

In 1973, Mondale’s comment was a punch line. Come 2025, it is not at all clear that any of Trump’s perceived enemies will find it a laughing matter.