OJ Simpson and the Bloody-Glove Defense

Jeffrey Toobin The New Yorker O.J. Simpson on June 15, 1995 in Los Angeles. (photo: Sam Mircovich/Reuters)

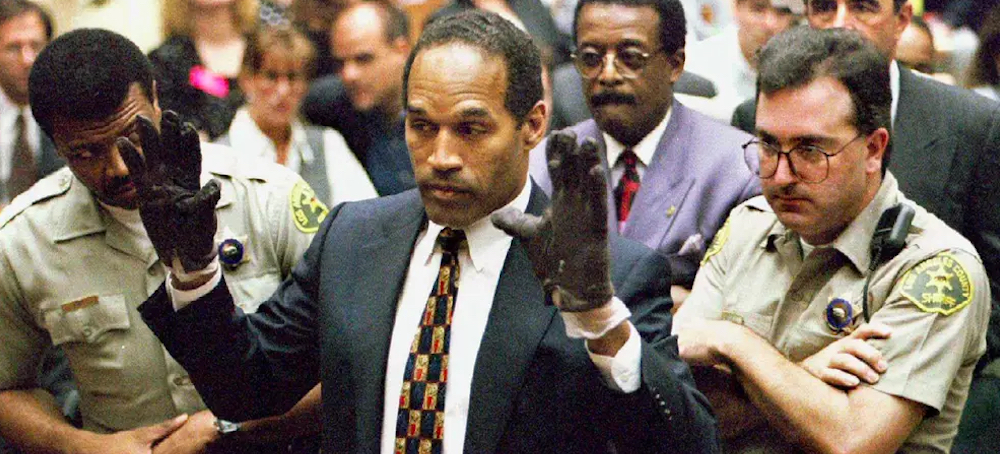

O.J. Simpson on June 15, 1995 in Los Angeles. (photo: Sam Mircovich/Reuters)

A surprising and dangerous defense strategy under consideration by O. J. Simpson’s legal team, led by Robert Shapiro, centers on Detective Mark Fuhrman, the police officer who jumped over Simpson’s wall—and found the bloody glove.

He does now—Mark Fuhrman. In a series of conversations last week, leading members of Simpson’s defense team floated this new and provocative theory as part of both the public-relations war surrounding the case and their continuing effort to keep the prosecution off balance. Those conversations revealed that they plan to portray the detective as a rogue cop who, rather than solving the crime, framed an innocent man. “Just picture it,” one of the attorneys told me. “Here’s a guy who’s one of the cops coming on the scene early in the morning. They have the biggest case of their lives. But an hour later you’re told you’re not in charge of the case. How’s that going to make that guy feel? So now he’s one of four detectives heading over to O. J.’s house. Suppose he’s actually found two gloves at the murder scene. He transports one of them over to the house and then ‘finds’ it back in that little alleyway where no one can see him.” That would make him “the hero of the case,” the attorney said.

At one level, it is a brilliant theory. It’s what some defense lawyers call a “judo defense,” in that it turns the strength of the prosecution’s case against the prosecution. The fact that the blood on the glove is consistent with the victims’ blood goes from being strong evidence of Simpson’s guilt—who else but Simpson could have been at both Nicole’s house and his own that night?—to being evidence of a police conspiracy. (However, if Simpson’s blood is found on the gloves, the defense theory will be harder to maintain.) If it was Fuhrman who transported the glove, then the bloody gloves become, for the defense, harmless at worst and exculpatory at best. That the Simpson defense team is advancing this theory shows just what kind of hardball it plans to play at the trial. For the theory, while ingenious, is also monstrous. It means that the defense will attempt to persuade a jury of Los Angeles citizens that one of their own police officers planted evidence to see an innocent man convicted of murder and, potentially, sent to the gas chamber.

In fact, the defense’s theory is even more monstrous. The defense will assert that Mark Fuhrman’s motivation for framing O. J. Simpson is racism. “This is a bad cop,” one defense lawyer told me. “This is a racist cop.” That would be an explosive allegation in any community, but it has a special resonance in Los Angeles. It was, of course, several officers in the Los Angeles Police Department who administered the notorious videotaped beating of Rodney King, in 1991—and it was the acquittal of those cops of state charges, in 1992, that prompted rioting in the city. For all the interest in the Simpson case, it has so far been regarded, particularly in Los Angeles, as a largely apolitical event. Its public impact has been, if anywhere, on the issue of domestic violence, not race relations. The wares of the T-shirt salesmen in front of the Los Angeles Criminal Courts Building last week included “Save O.J.” and “Let the Juice Loose!” models, but the same people were also selling shirts that said, “Remember Ron and Nicole.” One vender told me, “It’s all about business for us here, not politics.”

If race does become a significant factor in this case—if the case becomes transformed from a mere soap opera to a civil-rights melodrama; that is, from the Menendez brothers writ large to Rodney King redux—then the stakes will change dramatically. Simpson’s attorneys understand the implications of a racially tinged strategy, and there appear to be subtle but real differences of opinion within the defense camp about how hard to push the race angle. One Simpson attorney asserts that, while his client does appear to be the victim of a racist cop, the team will not claim that he was framed unless it truly believes he was. Another says that the Fuhrman defense is a done deal. Still, it appears that the case is about to enter a new phase—one with the potential to affect the city of Los Angeles as a whole, and not just one of its most famous residents.

Mark Fuhrman was born on February 5, 1952, and grew up in Washington state. An older brother died of leukemia before Mark was born. Mark’s father was a truck driver and carpenter, and when Mark was seven his parents divorced. In 1970, Fuhrman joined the Marines. He served in Vietnam, as a machine gunner, and he thrived in the service until his last six months there. As Fuhrman later explained to Dr. Ronald R. Koegler, a psychiatrist, he stopped enjoying his military service because “there were these Mexicans and niggers, volunteers, and they would tell me they weren’t going to do something.” As a result of these problems, in 1975 Fuhrman left the Marines and went almost directly into the Los Angeles Police Academy.

Fuhrman excelled at the academy, finishing second in his class, and his career with the L.A.P.D. had a promising start. His early personnel ratings were high. One superior wrote, “His progress is excellent and with continued field experience he should progress into an outstanding officer.” But in 1977 Fuhrman’s assignment was changed to East Los Angeles, and his evaluations began to show some reservations. “He is enthusiastic and demonstrates a lot of initiative in making arrests,” a superior wrote at the time. “However, his overall production is unbalanced at this point because of the greater portion of time spent in trying to make the ‘big arrest.’ ” Dr. Koegler wrote, “After a while he began to dislike this work, especially the ‘low-class’ people he was dealing with. He bragged about violence he used in subduing suspects, including choke holds, and said he would break their hands or face or arms or legs, if necessary.”

Fuhrman was moved into the prosecution of street gangs in late 1977, and, while his job ratings remained high, he later reported that the strains of the job affected him. “Those people disgust me, and the public puts up with it,” he told Dr. John Hochman, another psychiatrist, referring to his gang work. Fuhrman said that he was in a fight “at least every other day” and that he had to be “violent just to exist.” In just one year, he said, he was involved in at least twenty-five altercations in pursuing his duties. “They shoot little kids and they shoot other people,” he told Dr. Hochman. “We’d catch them and beat them, and we’d get sued or suspended.” In fact, Fuhrman was sued for his actions during this period. A man named Mario Carillo said that on October 16, 1978, he was stepping onto his sister’s porch when Fuhrman and another officer jumped out of their car and threw their batons at him. According to the civil lawsuit that Carillo filed against Fuhrman, the other officer, and the L.A.P.D., Carillo “ran inside the residence for protection and the police officers forced their way in and beat him.” (The case never came to trial and was ultimately dismissed, in 1985, when it appeared that Carillo was out of the country.) In any event, Fuhrman told Dr. Hochman, “That job has damaged me mentally. I can’t even go anywhere without a gun.” He explained, “I have this urge to kill people that upset me.”

The stress of police work took such a toll that, in the early nineteen-eighties, Fuhrman sought to leave the force. At the time, his lawyers asserted that in the course of his work he “sustained seriously disabling psychiatric symptomatology” and as a result should receive a disability pension from the city. To get that pension, Fuhrman waged an extended legal battle. The extensive case file, replete with detailed psychiatric evaluations of the officer (it is part of the public record), is paradoxical. In Fuhrman’s own briefs, he is portrayed as a dangerously unbalanced man; as one of them puts it, Fuhrman is “substantially incapacitated for the performance of his regular and customary duties as a policeman.” In the city’s answers, however, he is called a competent officer, albeit one involved in an elaborate ruse to win a pension. Dr. Hochman observed, “There is some suggestion here that the patient was trying to feign the presence of severe psychopathology. This suggests a conscious attempt to look bad and an exaggeration of problems which could be a cry for help and/or overdramatization by a narcissistic, self-indulgent, emotionally unstable person who expects immediate attention and pity.” In neither case—whether Fuhrman is a psychotic or a malingerer—is the picture of him an attractive one. He lost his case, and, as a result, is still on the force.

Simpson’s lawyers say that they are continuing a vigorous investigation of Fuhrman’s past. “We are hearing things that are unbelievable,” one of the lawyers told me. In fairness to Fuhrman, the proposition that he planted the glove on Simpson’s property may be just that—unbelievable. An L.A.P.D. spokesman told me last week that there was no public record of any disciplinary proceedings against Fuhrman. Fuhrman and all other members of the L.A.P.D. are under orders not to answer press questions about the Simpson case. I did, however, speak briefly with him on the telephone last week, and I asked him whether he had planted the glove on Simpson’s property. “That’s a ridiculous question,” he said. But did he do it? “Of course it didn’t happen,” he said. When I asked whether he had ever been sued for civil-rights violations, Fuhrman said that he could not speak further with me, and ended the conversation. It is true that the public record of Fuhrman’s career since he was denied his disability pension is uniformly favorable. In 1989, he helped arrest the former chief fund-raiser of a major charity for burglarizing post-office boxes, for which the man was convicted. In 1991, he was involved in the case against two University of Southern California football players in connection with a string of robberies and beatings. Later that year, he helped investigate two Santa Monica men who were charged in connection with as many as twenty-five muggings of elderly people. Simpson’s lawyers, led by Shapiro, will have the task of persuading a jury—or, at least, part of a jury—that such a man could be capable of a heinous form of official misconduct.

The projected attack on Fuhrman is just part of a concerted defense strategy to portray Simpson as a victim—of official misconduct and, in a larger sense, of his race. For one thing, the Simpson defense team is considering diversifying its own ranks. One Simpson lawyer told me that the team was negotiating with Johnnie L. Cochran, a prominent black litigator in Los Angeles, to join Shapiro on the trial team. The team is also at work on a motion, perhaps to be filed as early as this week, that will begin to lay out some of the perceived unfairnesses to Simpson. The motion will allege that the police mishandled the crime scene, making it impossible for the defense to conduct its own forensic tests of blood and hair samples. “Nobody was living at the house or planning on selling it at the time, but still they cleaned up the scene and made it impossible to pick our own samples of what was there,” one of Simpson’s lawyers told me. The defense will also allege that the prosecution is unfairly refusing to share the blood and hair samples that it did seize. “We want to make our own independent examinations,” the Simpson lawyer said. “Even if it’s not a fifty-fifty split, we should be allowed at least a third, or something reasonable like that.” The defense will assert, further, that there was additional tampering with evidence, beyond the placing of the second glove at Simpson’s house. Finally, Simpson’s lawyers will ask the judge to give an unusual instruction to the jury: that because of prosecution errors the defense was not allowed to conduct a full range of forensic tests on the evidence. All these claims, like the Fuhrman frameup theory, have a judolike appeal. Bad evidence becomes good; if Simpson’s own tests fail to exonerate him, the defense can argue that it was because it was not given access to adequate raw material. If the government’s tests tend to show guilt, then the government wasn’t playing fair.

Some—perhaps much—of the defense team’s newly aggressive posture may be nothing more than grandstanding. For all its bravado this week, the defense has not foreclosed any option, including a claim that Simpson did kill his ex-wife and Goldman but was suffering from some sort of insanity at the time. Even a plea bargain remains a possibility, though the defense attorneys state that they (and especially their client) have made and will make no overtures in securing one. By one reckoning, the new strategy may simply be a sign of desperation; the race card may be the only one in Simpson’s hand. But it appears that his defense team will be playing it, even if it means that helping O. J. Simpson threatens the tender peace of the city of Los Angeles. To Alan Dershowitz, one of Simpson’s legal strategists, such a tradeoff may well be worth making. In his book “The Best Defense” he wrote, “Once I decide to take a case, I have only one agenda: I want to win. I will try, by every fair and legal means, to get my client off—without regard to the consequences.

This piece originally appeared in The New Yorker, July 18, 1994.