Is Hunter Biden a Scapegoat or a Favored Son?

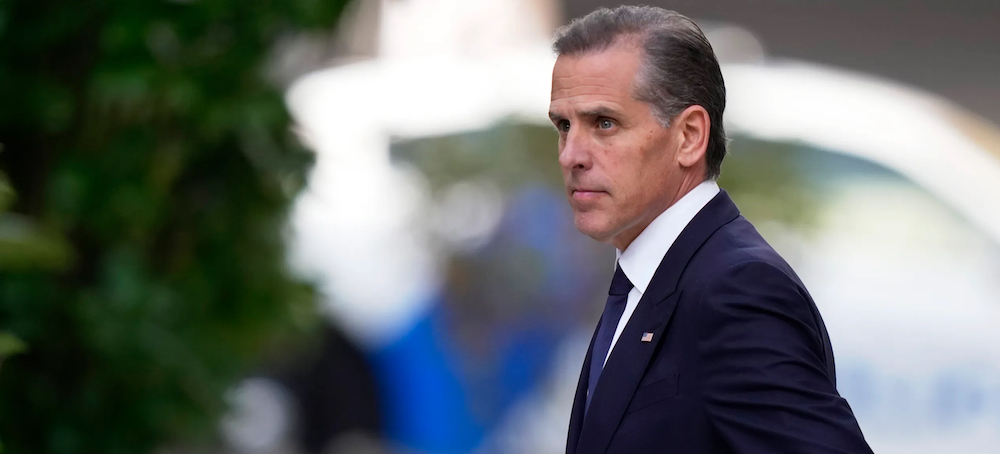

Katy Waldman The New Yorker Hunter Biden. (photo: Matt Slocum/AP)

Hunter Biden. (photo: Matt Slocum/AP)

The portrait that has cohered at his Wilmington trial is of a precious commodity, a man whom others conspire lovingly to shield.

The same coziness—now curdled—hung about several of the Delawareans called to testify. The prosecution’s marquee witness, Hallie Biden, the widow of Hunter’s brother Beau, met Beau in middle school. As Hunter writes in his memoir, “Beautiful Things,” Beau’s death, from brain cancer, in 2015 upended the family’s lives. Hunter, who’d already grappled with alcohol issues, became addicted to crack and sought out his sister-in-law for comfort. The two fell into a grief-stricken romance. Hallie was dear friends with Kathleen Buhle, Hunter’s first wife, to whom he was still married at the time; Buhle’s daughters—Hallie’s nieces—found evidence of the affair in 2017. The characters in the tragedy are uncomfortably close together, as in an awkward family photo, and the dynastic incestuousness of the situation lends it a gothic quality.

Hallie was brought in by the prosecutors to testify that Hunter had been in the throes of a crack-cocaine addiction in October, 2018, the month he bought the gun. She may have been the person closest to the defendant at that time; a flurry of contemporaneous texts she’d sent him was introduced as evidence of his battle with drugs. Dressed conservatively in black pants and a white blouse, Hallie watched as her private anguish was projected onto a giant screen. She had remarried the weekend before the trial, and she fidgeted nervously with the conspicuous sparkle on her ring finger. “You ok? Where r u,” she’d written Hunter, on October 13, 2018. On October 15th, she wrote, “I just want to help you get sober, nothing I do or you do is working. I’m sorry.” On October 23rd, she pleaded, “I just want you safe.” On November 8th, she urged him to return to the house and begin treatment: “Come home and talk with the kids,” she implored. “Let’s tell your family and your kids the plan and let’s stick to it.”

Speaking softly, Hallie described discovering Hunter’s gun in his truck, on the morning of October 23rd. She’d been trying to get in touch with him for weeks, she claimed, when he staggered into the house early in the morning and went to bed. After dropping her kids off at school, she returned home to perform a familiar ritual, one also recounted by Buhle when she took the stand: that of searching her partner’s car for drugs. Ms. Biden found the Colt .38, in a box with a broken lock, amid crack remnants and other paraphernalia strewn around the car. Horrified, she grabbed a purple gift bag from the house, placed the gun inside, drove two minutes to an upscale supermarket called Janssen’s, and tossed the package into a garbage receptacle outside.

“I realize it was a stupid idea now, but I was just so panicked,” she told the lawyer Leo Wise, who was examining her. “I didn’t want him to hurt himself, or the kids to find it and hurt themselves.” When Hunter discovered that his gun was missing, text messages show, he insisted that Hallie go back to retrieve the parcel from the trash can. But, by that time, the gun had been lifted by an eighty-year-old man looking for recyclables. Hunter pressed Hallie to file a police report and she agreed. “I’ll take full blame,” she wrote, “I don’t want to live like this anymore.”

Between the lines of Hallie’s testimony, a picture of Hunter’s community emerged—a privileged, insular world, full of supporting figures primed to protect him from himself. This impression was echoed by the testimony of police officers assigned to investigate the stolen-weapons complaint. As they discussed working assiduously with local Delawareans to recover Hunter’s property, it was easy to forget that the Biden son was in court not as the victim of a crime but as the alleged perpetrator of one.

The federal law that Hunter was arrested for breaking—the Gun Control Act of 1968, which prohibits felons, illegal-drug users, and the mentally incompetent from buying guns—is “seldom prosecuted as a standalone charge,” according to the Times, and has drawn scrutiny for its racist history. Proponents argue that the statute helps remove perpetrators of violent crime from the streets; in any case, it’s rarely used against nonviolent offenders, like Hunter (or like Donald Trump, who surrendered two firearms registered in his name to the N.Y.P.D. last year when criminal charges were brought against him, and whose reported remaining gun, in Florida, may be seized now that he’s a felon). A genuine shadow lies across Hunter’s business dealings, but—to echo Logan Roy, another paterfamilias surveying the wreckage wrought by his kids—this is not a serious trial. Hunter Biden allegedly possessed an illegal gun, but only for eleven days; the gun was never fired, and it wound up in a trash can; the defendant allegedly committed the felony five years ago and has no prior convictions. In the summer of 2023, a Trump-appointed judge, Maryellen Noreika, capsized a plea deal that would have swept the weapons charges away, leaving two misdemeanor charges of tax evasion. The upshot is that the child of a sitting President is facing a possible twenty-five-year prison sentence for a charge that smacks of theatre and opportunism.

But if Hunter is bearing the weight of Republicans’ displeasure with their Commander-in-Chief, it is hard to fully internalize the image of him as a scapegoat. The portrait that has cohered at his trial is of a precious commodity, a man whom others conspire lovingly to shield. Hunter is often invoked as the black sheep of his family, but he emerged, through layers of deposition, as one of Wilmington’s golden sons, an object of collective anxiety and concern. His weapon terrified Hallie, she told the jury, because it posed a threat to him and to her children—the two catastrophes summoned in a single breath.

Often, it seems to have fallen to the women in Hunter’s life to help carry his pain. Buhle supported him through alcoholism for years before he cheated on her. (In 2021, a court ruled that he owed her $1.7 million in unpaid alimony and legal expenses.) On Wednesday, the prosecution summoned a dancer named Zoe Kestan, with whom Hunter had a relationship, to recount how he would vow to get clean and then backslide. Meanwhile, he’d send her on errands—withdrawing cash, buying clothes for his children. On Friday, Hunter’s daughter Naomi wrenchingly described trying to spend time with her dad while he was using. In a text message provided by the prosecution, she wrote, “I can’t take this . . . I just miss you so much.”

If Hunter’s network of women helped him redistribute the agony of his addiction, they also helped him redistribute the blame for it. One of his texts, about an unidentified woman, reads, “I blame her for being a selfish self righteous hypocritical cunt that actually truly works against my getting sober.” Hunter frequently opined on the inadequacies of his brother’s widow as a nurturer and helpmate; Hallie pressed him to seek treatment, text messages show, and he responded with silence or anger, at times berating her for failing to prop him up. “What one thing have YOU done to help me get sober,” he asked. On October 23rd, when Hallie confessed to him that she had got rid of his revolver, he declared her “insane” and “totally irresponsible and unhinged.” “The fucking FBI Hallie,” he also texted. “It’s hard to believe anyone is that stupid // so what’s my fault here Hallie that you speak of. Owning a gun that’s in a locked car hidden on another property? You say I invade your privacy. What more can I do than come back to you to try again. And you do this???? Who in their right mind would trust you would help me get sober?”

Hunter has a point: if Hallie wished to protect him, she should not have taken a gun registered in his name and thrown it into a public trash can. But there’s nothing irrational about her fear that he might use the pistol to harm himself. Suicides are the most common form of firearm death, and Hunter’s messages reveal someone crashing against rock bottom: he wrote to Hallie that he was a “drunk” and an “addict” who has “ruined every relationship I’ve ever cherished,” in language echoing her own account of using drugs with him during the summer of 2018. “It was a terrible experience that I went through,” she told the jury, “and I am embarrassed, and I am ashamed, and I regret that period of my life.” The difference between Hallie’s descent into hell and Hunter’s appears to be that Hallie spent much of her trip worrying about her partner.

There’s a fundamental duality to addiction. It can be a story of both self-destruction and self-swelling entitlement. Hunter’s life is full of such oxymorons. As rates of substance abuse have soared in recent years, especially during the pandemic, the fifty-four-year-old can be seen as in some ways representative, and potential jurors on Monday likened him to their own loved ones who’ve suffered from addiction. But in other ways, of course, Hunter is an outlier, with a warehouse of resources and second chances that most people who struggle with drugs or alcohol can only dream of. In the Biden cosmological model, he may spin off to the side of Beau, the heir, but he is still more central than Beau’s grieving widow, or any of the other ancillary characters who appeared at the trial.

The day that Hunter’s trial began the President put out a loving but careful statement of support for his son. “Jill and I love our son,” the message read in part, “and we are so proud of the man he is today.” At the same time, Biden has made clear that he will not pardon Hunter if he is convicted. This balancing act speaks to another duality that the Bidens must contend with—they have to navigate not only the delicate diplomacy of the family system but also the trip wires of the political one. As far as a kid is concerned, a father can do anything, even rearrange the heavens to give one of his children more time in the sun. A President’s powers, it seems, are far more limited.