How Kamala Harris Can Beat Donald Trump on the Debate Stage

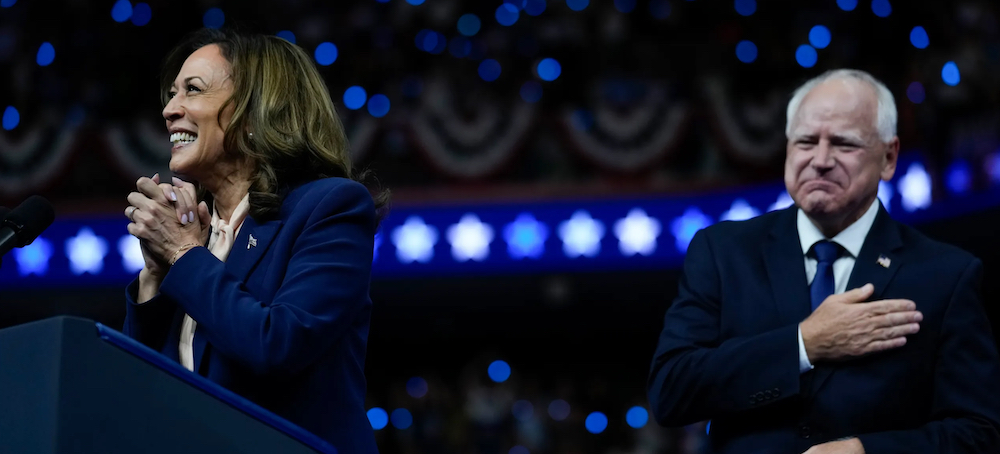

Jessica Winter The New Yorker Democratic presidential nominee Vice President Kamala Harris and her running mate Minnesota Gov. Tim Walz speak at a campaign rally in Philadelphia, Tuesday, Aug. 6, 2024. (photo: Matt Rourke/AP)

Democratic presidential nominee Vice President Kamala Harris and her running mate Minnesota Gov. Tim Walz speak at a campaign rally in Philadelphia, Tuesday, Aug. 6, 2024. (photo: Matt Rourke/AP)

In the Vice-President’s previous debate triumphs, she did not conquer her opponents so much as she permitted them to lose.

It’s true that, during the stuffed-phone-booth Presidential-primary debates of 2019, Harris hardly distinguished herself among the candidates. (Nobody did, save for Bernie Sanders, whose unwavering message discipline often seemed to be the only anchor in a chaotic sea.) Yet, even then, Harris managed to create a viral moment. In calling out Joe Biden’s historical opposition to federally enforced busing as part of school-desegregation efforts in the nineteen-seventies, she summoned an image of a little Black girl who, along with her schoolmates, found herself on the front lines of an ugly racial reckoning. “And that little girl,” Harris went on, “was me.” Two lecterns down, Biden looked up sharply, surprised. The moment was calculated and yet raw and rattled, too; like some of the best political theatre, it felt at once choreographed and improvised. It may have secured Harris’s place on Biden’s ticket in 2020, and, if it did, it made possible all that’s come since.

If Harris’s luck holds for her debate with Donald Trump, on Tuesday night in Philadelphia, it will not be thanks to the agreed-upon rules of the match, which blunt what would otherwise be her advantages. In the debates with Sanchez and Pence, Harris was able to project stately calm and patience during her opponents’ interruptions and constant disregard of the moderators’ attempts to enforce time constraints; she appeared to be the grownup in the room. Harris’s repeated admonishment of Pence in their debate—“I’m speaking”—became a refrain in an “S.N.L.” cold open (and resurfaced when Harris was interrupted by pro-Palestine demonstrators at a recent rally in Michigan). “If you don’t mind letting me finish,” she said to Pence at another point, smiling at him indulgently, “we can then have a conversation. O.K.?” Pence continued spluttering about “climate alarmists,” but that sparkly-eyed “O.K.?” put him back in his seat; in that exchange, she was not debating him so much as managing him, like a sure-handed teacher would do with an unruly grade-schooler.

Pence is a model of decorum compared with Trump. But, in Tuesday’s debate, the candidates’ microphones will be muted whenever it’s not their turn to speak, which may deliver a deceptively restrained, genteel facsimile of Trump to the television audience. The lack of hot mikes may also stymie some of the open verbal sparring between the candidates, giving Harris less of an opportunity to go on the offensive against Trump in the prosecutorial style that she wielded in Senate hearings with the likes of Bill Barr, Brett Kavanaugh, and Jeff Sessions.

A somewhat muffled debate format may also frustrate one of the Vice-President’s subtler strengths: how she underscores her opponents’ foibles through the means of her own wry, contagious amusement. Against Sanchez, Harris’s laughter was a veil for pity and dismay. Against Pence, her incredulous smile expressed a righteous, controlled fury at his bland lies and obfuscation. Sometimes, though, Harris’s various shades of mirth simply add ironic merriment to proceedings that otherwise slog along. In one of the 2019 primary debates, Andrew Yang, in his opening statement, offered ten viewers at home the chance at a monthly thousand-dollar “freedom dividend” if they visited his Web site; the pitch had the whiff of a bribe, may have violated Federal Election Commission rules, and delighted several of Yang’s fellow-candidates. (Amy Klobuchar started clapping.) Harris, true to her brand, laughed and kept laughing. When the camera cut to a bemused Pete Buttigieg, the next Democrat in line to deliver opening remarks, Harris could still be heard cracking up offscreen, her laughter falling lightly on the mayor of South Bend like a warm spring rain.

On August 29th, Harris and Governor Tim Walz, of Minnesota, sat down with CNN’s Dana Bash for their first television interview as running mates. Harris recounted the Sunday morning when President Biden phoned her to say that he was withdrawing from his race for reëlection. At the time of the call, Harris said, she was at home with her little nieces; she’d fixed pancakes and bacon for breakfast, and they were sitting down to do a puzzle together. Harris drew a sweetly ordinary scene, and, as is too frequently the case, I thought of Donald Trump, for whom this domestic landscape might as well be the surface of the moon. One struggles to picture him preparing breakfast for a child or spreading jigsaw pieces out on a kitchen table. Such acts do not qualify a person to be President, but they evince a baseline of competency and care, of everyday love and togetherness. For the purposes of the debate with Trump, it’s difficult to imagine Harris botching the essential study in contrasts: prosecutor vs. criminal, yes, but also normie vs. weirdo, superego vs. id, adorable nieces vs. Large Adult Sons, homemade flapjacks vs. Trump Steaks.

Debates, for the most part, don’t matter, or so we are told. The debacle of Biden-Trump II was the exception that proves the rule—to meet the threshold for mattering, a sitting President must spontaneously combust on live TV. Hillary Clinton objectively trounced Trump in all three of their debates (and was physically menaced by him in one of them) and it didn’t matter. George W. Bush and Barack Obama were bulldozed in their first outings against John Kerry and Mitt Romney, respectively, and it didn’t matter. And it is disquieting to revisit Biden’s many lacklustre, halting debate performances in the crowded primary that he eventually won. It stands to reason that, although a debate made Harris the nominee, a debate will not win or lose her the Presidency. Still, Tuesday’s debate matters more than most: because of its cataclysmic predecessor; because it might be the only one between Harris and Trump; and because Harris’s campaign window has been so narrow. She is still in the process of introducing herself to voters, solidifying her policy outlook, and establishing her charisma—the star of any stage needs to show both strength and vulnerability, confidence and humility, gravitas and good humor.

Trump’s superpower is his uncanny anti-charisma: he’s the whining-baby strongman, the self-dealing populist, the scammer and bankruptcy-court veteran whom more Americans trust on the economy, the standup comedian who has never laughed. He demands a good heckling, and, even without the benefit of a hot mike, one suspects that Harris can goad him into heckling himself—of laying out the prosecutor’s case on her behalf by dint of his own logorrhea. It may be comforting to Harris’s partisans that, to a great extent in her major one-on-one debate triumphs, she did not conquer her opponents so much as she permitted them to lose. She had only to stand graciously back, beaming encouragement their way.