God Save Us From This Dishonorable Court

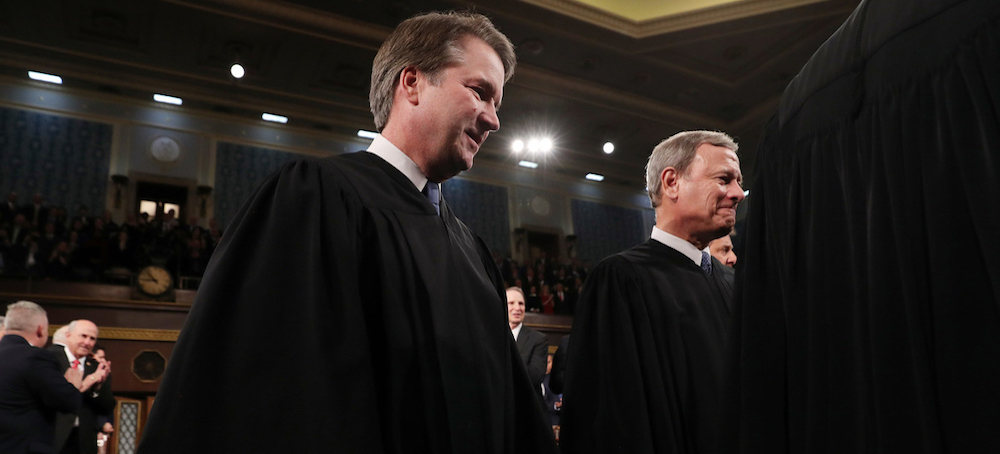

Ruth Marcus The Washington Post Justice Brett Kavanaugh and Chief Justice John Roberts. (photo: Getty Images)

Justice Brett Kavanaugh and Chief Justice John Roberts. (photo: Getty Images) God Save Us From This Dishonorable Court

Ruth Marcus The Washington Post

An egregious, unconscionable ruling on presidential immunity from the Supreme Court.

If I sound worked up, it is because a six-justice majority opinion in the aptly named Trump v. United States is bad beyond my wildest imaginings. The court might have had legitimate concerns about the implications of its rulings not for Trump but for future presidents who might be chilled in exercising their constitutional duties by the prospect of criminal prosecution, and the consequent “enfeebling of the Presidency.” It is correct that “we cannot afford to fixate exclusively, or even primarily, on present exigencies.”

But the opinion, written by Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr., went way further than necessary to insulate Trump from prosecution — not simply before the election, which the court, by its lassitude, had nearly guaranteed, but forever, even in the event that President Biden wins reelection. The court could have carved out an oasis of protection for reasonable presidents engaging in reasonable executive actions. It chose not to.

Instead, as the dissenting liberal justices said, it has “replaced a presumption of equality before the law with a presumption that the President is above the law for all of his official acts” and created “a law-free zone” protecting the president: immunity for deploying Seal Team 6 to assassinate a rival, for organizing a military coup to retain power, for taking a bribe in return for a pardon.

“Let the President violate the law, let him exploit the trappings of his office for personal gain, let him use his official power for evil ends,” Justice Sonia Sotomayor wrote for herself and Justices Elena Kagan and Ketanji Brown Jackson. “Because if he knew that he may one day face liability for breaking the law, he might not be as bold and fearless as we would like him to be. That is the majority’s message today.”

The majority accused the dissenters of striking “a tone of chilling doom that is wholly disproportionate to what the Court actually does today” and “fearmongering on the basis of extreme hypotheticals.” It proclaimed that the president “is not above the law.”

Then it squarely placed him there.

Let’s assess: When Trump’s lawyers first raised the far-fetched notion that a president has absolute immunity from criminal prosecution for his criminal acts, it seemed like more of a canny bid to delay Trump’s trial on charges of election interference beyond November than a serious constitutional argument.

That’s because every previous court to have considered the question, as well as every Justice Department legal opinion, had assumed that presidents are subject to criminal prosecution for their official acts. As the court recognized, Alexander Hamilton wrote in Federalist No. 69 that presidents would be “liable to prosecution and punishment in the ordinary course of law.” Richard M. Nixon accepted Gerald Ford’s pardon for that very reason. Trump’s own lawyers argued at his second impeachment trial that he was subject to criminal prosecution, and shouldn’t be convicted for that reason.

And let’s be clear: Before Monday’s ruling, no previous president imagined that he had immunity from criminal prosecution — and they somehow managed to engage in plenty of “bold and unhesitating action.”

The case on which Trump’s lawyers founded their shoot-the-moon claim was the Supreme Court’s 1982 ruling in Nixon v. Fitzgerald. In that case, a Pentagon whistleblower sued the former president, claiming he had been dismissed in retaliation for his congressional testimony about cost overruns.

The court ruled 5-4 that presidents possess absolute immunity from civil suits for damages arising out of their official conduct, and it adopted a broad view of official acts, saying that protection applies to any conduct “within the outer perimeter” of a president’s responsibilities.

But the court emphasized the distinction between the harassment potential of civil suits, noting the “lesser public interest in actions for civil damages than … in criminal prosecution.”

On Monday, the majority hijacked the Fitzgerald ruling to transplant its reasoning into the very different criminal context. “The danger is akin to, indeed greater than, what led us to recognize absolute Presidential immunity from civil damages liability — that the President would be chilled from taking the ‘bold and unhesitating action’ required of an independent Executive,” Roberts warned.

The majority went on to carve out an expansive sphere of presidential immunity. Its approach was doubly problematic: both in the broad theory it set out and the precise way it applied those newly concocted protections to Trump’s behavior.

As an initial matter, do not be conned by the majority’s smug declaration that presidents remain subject to being prosecuted for their private acts. No one — not even Trump’s lawyers — argued that. So, thanks, but no thanks.

The court laid out two kinds of immunity — both unwarranted.

First, the court said, the president has absolute immunity from prosecution for actions within his “core” constitutional powers — things such as issuing pardons, naming ambassadors or vetoing laws.

On this score, as the dissenters noted, the majority’s view of core powers “expands the concept of core powers beyond any recognizable bounds.” This core power, the dissent said, is so broad — it includes the president’s duty to take care that the laws are faithfully executed — that it would “effectively insulate all sorts of noncore conduct from criminal prosecution.”

As an example, the dissenters cited the court’s assertion that Trump’s discussions with Justice Department officials fell within the protections of absolute immunity. “Under that view of core powers, even fabricating evidence and insisting the Department use it in a criminal case could be covered,” Sotomayor wrote.

Second, the court said, the president enjoys “presumptive” immunity even for other official acts outside those core powers. Here, too, the majority found ways to interpret that category broadly and to make the presumption as unassailable as possible. The majority’s definition of official includes anything “not manifestly or palpably” beyond presidential authority. In addition, it said, courts can’t look into presidential motives to distinguish between official and unofficial acts.

As the dissenters pointed out, “Under that rule, any use of official power for any purpose, even the most corrupt purpose indicated by objective evidence of the most corrupt motives and intent, remains official and immune.”

Wait, there’s more: Even when prosecutors go after unofficial acts, they can’t use evidence of any official acts as part of their proof the former president committed a crime. This part was too much for Justice Amy Coney Barrett, who did not join that part of the majority.

Sotomayor helpfully explained the consequences of this overreach. “Imagine a President states in an official speech that he intends to stop a political rival from passing legislation that he opposes, no matter what it takes to do so (official act). He then hires a private hitman to murder that political rival (unofficial act),” she wrote. “Under the majority’s rule, the murder indictment could include no allegation of the President’s public admission of premeditated intent to support the [charge] of murder.”

Equally if not more problematic was the way the majority applied its holding to the fact of Trump’s case. It went out of its way to carve out protections for him.

His pressuring of Vice President Mike Pence not to certify the election results? “Whenever the President and Vice President discuss their official responsibilities, they engage in official conduct,” the majority said. So, “Trump is at least presumptively immune from prosecution for such conduct,” and it’s up to the special prosecutor to prove otherwise.

Trump’s efforts to get allies to submit slates of fake electors? The former president’s lawyer conceded at oral argument that was a private act, then maybe took it back. The majority wasn’t so sure: “The necessary analysis is instead fact-specific, requiring assessment of numerous alleged interactions with a wide variety of state officials and private persons.”

Astonishingly, the court congratulates itself for the speed with which it handled the case — “less than five months” — and takes the lower courts to task for moving, believe it or not, too quickly. “Despite the unprecedented nature of this case, and the very significant constitutional questions that it raises, the lower courts rendered their decisions on a highly expedited basis,” Roberts wrote.

And, if that wasn’t enough, Justice Clarence Thomas gave a you-go-girl push to U.S. District Judge Aileen M. Cannon in Florida, who heard arguments last week about whether special counsel Jack Smith’s appointment was illegal. Though the issue never came up in the pending case — except for Thomas raising a question about it at oral argument — the justice’s concurrence devoted nine pages to bolstering the contention that Smith’s appointment violates the Constitution.

“If this unprecedented prosecution is to proceed, it must be conducted by someone duly authorized to do so by the American people,” wrote Thomas. “The lower courts should thus answer these essential questions concerning the Special Counsel’s appointment before proceeding.” Hint, hint. This from a man whose wife’s involvement with the Stop the Steal movement should have meant he had no business hearing this case.

Smith’s office is now consigned to assess the tatters in which the court’s ruling has left its prosecution and determine, like a homeowner after a tornado has touched down, what can be salvaged.

The country is now left to worry about whether Trump will ever be held accountable — and about the implications of the court’s ruling for future presidents, including, most chillingly, Trump himself.

As Jackson wrote in a separate dissent, “Having now cast the shadow of doubt over when — if ever — a former President will be subject to criminal liability for any criminal conduct he engages in while on duty, the majority incentivizes all future Presidents to cross the line of criminality while in office, knowing that unless they act ‘manifestly or palpably beyond [their] authority,’ they will be presumed above prosecution and punishment alike.”

Sotomayor was similarly apocalyptic. “With fear for our democracy, I dissent,” she closed her dissent. Both Sotomayor and Jackson abandoned the customary “respectfully” — for good reason.

God knows what a reelected Trump would do in a second term. God save us from this dishonorable court.