Brett Kavanaugh Is Using the Logic of Dobbs to Pursue a Dangerous New Agenda

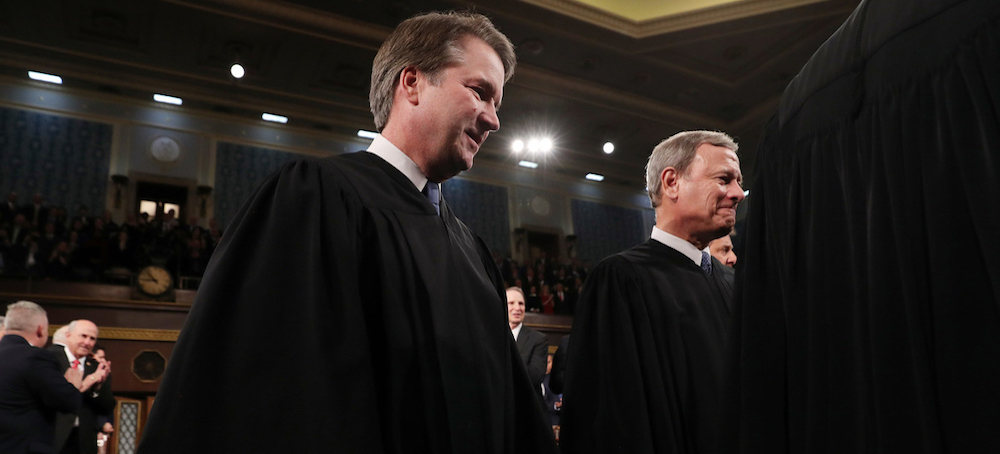

Dahlia Lithwick and Mark Joseph Stern Slate Justice Brett Kavanaugh and Chief Justice John Roberts. (photo: Getty Images)

Justice Brett Kavanaugh and Chief Justice John Roberts. (photo: Getty Images)

Skrmetti is a challenge to a Tennessee law known as S.B. 1 that seeks to block health care for transgender youth. The statute bars doctors from providing puberty blockers or cross-sex hormones to trans children, although these and other gender-affirming medicines remain freely available to cisgender kids. A cisgender boy who wants testosterone to kick off the development of male sex characteristics can still get it. A transgender boy who wants testosterone for the exact same reason cannot. The only difference between the two is that the transgender boy was deemed female at birth. So, the plaintiffs argue, S.B. 1 plainly discriminates on the basis of sex, and is therefore subject to heightened scrutiny, requiring Tennessee to put forth an “exceedingly persuasive justification” for its restrictions, otherwise it is unconstitutional. Half a century of gender discrimination jurisprudence demands this result.

That’s all the court needed to do in Skrmetti: acknowledge that S.B. 1 treats people differently because of sex, then send the case back down to the lower court to determine if that discrimination is nevertheless justified by a strong state rationale. On Wednesday, however, most of the conservative justices signaled that they have a different plan in mind. They seem eager to transform this case into a spiritual successor to Dobbs, directly analogizing transgender rights to abortion rights, and prohibiting courts from stepping in because the Constitution is “neutral” on the subject. After aggressively intervening in the democratic process on their own pet issues—including those, like gun safety and pandemic laws, with life-or-death stakes—these same justices want to retreat behind a deference to legislatures to do what they deem best.

Justice Brett Kavanaugh best captured this posture when he reprised the ode to “neutrality” that he debuted in Dobbs. “It seems to me that we look to the Constitution, and the Constitution doesn’t take sides on how to resolve that medical and policy debate,” he lectured Solicitor General Elizabeth Prelogar, who, alongside the American Civil Liberties Union, argued against the ban. “The Constitution’s neutral on the question.” Prelogar immediately shot back: “I do think that the Constitution takes a position that individuals are entitled to equal protection of the law.”

Kavanaugh then pivoted, harping on “detransitioners”—people who transitioned, and then stopped identifying as transgender. In reality, very few people ever “detransition.” But Kavanaugh put them front and center, a possible effort to delegitimize transgender identity, or at least overstate the ostensible dangers of these treatments. This is a direct callback to Justice Anthony Kennedy, who rooted his hostility toward reproductive rights in women who come to regret their abortions. Again, cases of such regret are vanishingly few, but the implication is that so long as one person can be found to regret a decision, it should be barred for everyone. Kavanaugh brought up detransitioners again with Chase Strangio, the ACLU attorney arguing on behalf of the Tennessee families. Strangio, the first openly transgender person to argue at SCOTUS, had to explain to Kavanaugh that people sometimes regret getting treatments “in all areas of medicine,” not just with respect to gender-related care. The mere existence of detransitioners does not, as a matter of law, magically abolish the equal protection clause’s limits on sex discrimination in state regulation of health care.

One would imagine that, at least on occasion, someone regrets purchasing a gun as well. Yet the court’s conservative bloc has not claimed that this should be a reason to soften the protections of the Second Amendment.

Justice Samuel Alito, meanwhile, ignored the vast array of American medical associations that urged the court to strike down Tennessee’s ban in favor of … the national health care policies of European nations. The conservative legal methodologies practiced by Alito and the conservative legal movement typically counsel against reliance upon international laws in interpreting the U.S. Constitution. Yet Alito gave great weight to the Cass Review, a controversial U.K. report critical of gender-affirming care that excludes compelling evidence of its safety and efficacy. He scolded Prelogar for failing to engage with this document, at one point demanding: “Is it not true that you just relegated the Cass report to a footnote?” And then he harped on Sweden’s rollback of gender-affirming care for minors as though it somehow showed that the U.S. Constitution’s equal protection clause should not safeguard trans youth.

Prelogar was left to inform Alito that these countries have not actually imposed the total ban that Tennessee attempted here, nor did the Cass report call for such a sweeping ban. It’s the red states that are the outlier here, going much further than European countries to target the rights of trans youth and their families. So Alito tried again: “For the general run of minors, do you dispute the proposition, in fact, that in almost all instances, the judgment at the present time of the health authorities in the United Kingdom and Sweden is that the risks and dangers greatly outweigh the benefits?” Prelogar did “dispute that,” because these countries still say that “this care can be medically indicated for some transgender adolescents” using an “individualized approach.” A fuming Alito then insisted that “the current Labour government” in the United Kingdom was still implementing the Cass report, implying that this is the policy of a progressive government in greater Europe. We guess this is just what law looks like now: a justice shredding equal protection based on his half-baked conception of what’s happening across the pond.

If any of the conservatives might have posed genuinely helpful or illuminating questions, it would have been Justice Neil Gorsuch—who, after all, wrote the opinion in Bostock v. Clayton County, the landmark LGBTQ decision he penned that determined that “it is impossible to discriminate against a person for being … transgender without discriminating against that individual based on sex.” Going into arguments, the determinative question was whether Gorsuch would apply his reasoning in Bostock to this case. Would Chief Justice John Roberts, who agreed with him in Bostock, once again support the position protecting the rights of trans people? Yet bafflingly, Gorsuch refused to ask a single question Wednesday. His silence may indicate that he will quietly join an anti-trans opinion that ignores or curtails Bostock’s logic without explaining himself, retreating from his previous position now that the political environment has grown more hostile to trans equality. Roberts, for his part, evinced almost no sympathy toward the transgender patients who came to court asking only that their parents and physicians be allowed to guide their health care, promoting nearly boundless deference to the biases of state legislators instead.

At times, the liberal justices appeared to be palpably horrified at the implications of their colleagues’ questioning. Justice Sonia Sotomayor was compelled to explain the anguish and suffering of kids denied medical care, describing one child whose gender dysphoria made him throw up every day and go “almost mute.” Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson explicitly linked the logic floated by the conservative justices to that of cases like Loving v. Virginia that once allowed states to discriminate on the basis of race as long as they did so “equally” between races. Expect an opinion in Skrmetti that makes fatuous claims about the unknowability of medical science and how ill-suited judges are to decide complex, evolving health care questions from the same folks who cited Sir Matthew Hale, who sentenced women to death as “witches,” in their majority opinion in Dobbs. This case stands poised to roll back 50 years of gender discrimination doctrine based on the warped logic of Dobbs about the infinite wisdom of the democratic process and the ineffable mystery of medical science. In so doing it will throw open the door to yet more discrimination against trans adults, women, and other vulnerable groups.

This Supreme Court has in recent years weighed in decisively on many areas of unsettled science: COVID mitigation, the design of bump stocks, particulate matter in the air, the value of wetlands, even when life begins. It has put itself in the driver’s seat on federal regulation of matters vast and minute. But when the American medical establishment joins forces with patients and doctors to say that young people deserve access to gender-affirming care, the Supreme Court will tell you that the Constitution is “neutral” on the subject—an unknowable question of science that’s best left to the experts in the statehouses. For centuries we saw what happened when a court held itself out as “neutral” when it came to discrimination: More discrimination. Somehow, on Wednesday we find ourselves precisely where we started.