A Dangerous Game Over Taiwan

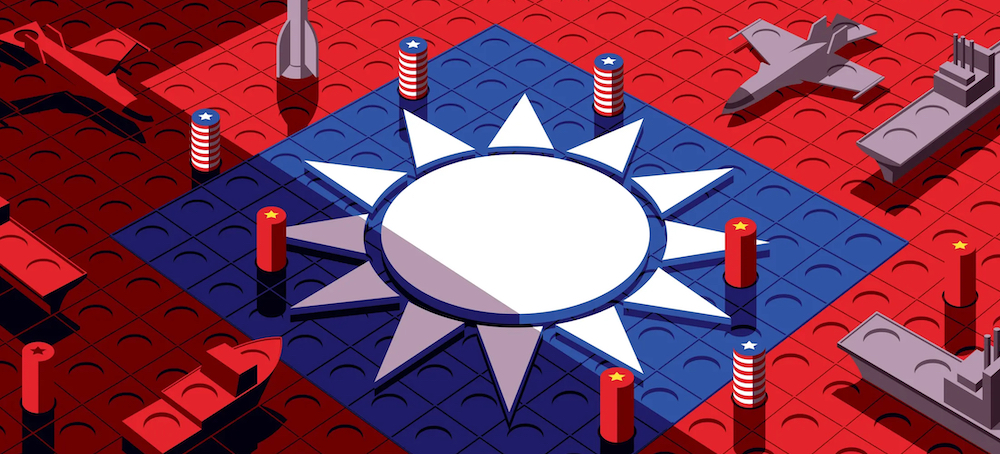

Dexter Filkins The New Yorker "This past summer, the fight for Taiwan flared again." (photo: Malika Favre/The New Yorker)

"This past summer, the fight for Taiwan flared again." (photo: Malika Favre/The New Yorker)

For decades, China has coveted its island neighbor. Is Xi Jinping ready to seize it?

In the nineteen-forties and fifties, Kinmen was the scene of ferocious assaults by Communist China as it tried to seize control. The invading forces, expecting an easy victory, were met with surprising resistance, from fighters dug in behind rows of steel spikes and in cement bunkers along the beach. Frustrated, the Chinese began bombarding Kinmen, flinging thousands of artillery shells across the water in the hope of forcing its people to surrender. When I visited not long ago, an eighty-year-old resident named Lin Ma-teng recalled hearing the shells as a young boy: “I used to hide under my bed.”

The shelling continued for decades. One day in 1975, when Lin was serving in a Taiwanese artillery unit, a shell exploded nearby, tearing off a chunk of his right thigh. He spent a year in the hospital and still walks with a limp. During my visit, he showed me rusting artillery shells that he has piled in his hallway—mementos of the long conflict between the fragile island democracy of Taiwan and the behemoth next door, which has never stopped trying to assert dominion. On the beach near Lin’s house, visitors can still see the bunkers and barriers, where people he knew in his youth fought the Chinese. They’re crumbling now. “Maybe the war is coming back,” he told me. “What would the people of Taiwan do? Jump into the ocean and swim?”

This past summer, the fight for Taiwan flared again. On June 13th, Wang Wenbin, a spokesman for the Chinese Foreign Ministry, declared that the People’s Republic had “sovereignty, sovereign rights, and jurisdiction” over the Taiwan Strait. Under international law, the strait has long been considered an open waterway; Wang was sweeping that away. “Taiwan is an inalienable part of China,” he said. Two weeks later, the People’s Liberation Army announced that it would hold a live-fire exercise seventy miles off the island’s coast. Then, on August 2nd, the House Speaker, Nancy Pelosi, arrived in Taiwan, making her the highest-ranking American official to visit in twenty-five years. As she greeted officials, an American aircraft carrier, the U.S.S. Ronald Reagan, loomed offshore.

Soon after Pelosi departed, the P.L.A. test-fired eleven Dongfeng ballistic missiles, which landed in waters around Taiwan; at least four flew over the island itself. Then the P.L.A. initiated a large-scale naval exercise, arraying warships outside Taiwan’s major ports. “The U.S. has made wanton provocations,” Wang said. That same week, Chinese fighter jets undertook flights down the Taiwan Strait, crossing the “median line,” the customary boundary between the two countries; each time, Taiwanese jets scrambled to confront them.

The crisis passed, but it gave some American officials a sense that a confrontation between the two nuclear-armed superpowers was dangerously possible. “It was scary,” a senior Biden Administration official told me. “Not because we thought the Chinese would invade, but we worried there might be an accident, with unpredictable actors all around.”

China’s leaders seized the moment to say that they were “normalizing” these kinds of encroachments. In the next two months, Chinese fighter jets crossed the median line more than six hundred times. The flights were “very close and very threatening,” Taiwan’s foreign minister, Joseph Wu, told me. Although China claimed that the maneuvers were a response to Pelosi’s visit, Taiwanese officials said that they had almost certainly been in the works for months.

These moves seemed designed to convince the Taiwanese people that their national existence—which grew out of the chaos of the Chinese Civil War, more than seventy years ago—was coming to an end. Physically, too, the provocations took a toll, wearing down the Taiwanese armed forces. “Whenever the Chinese send their planes up there, we have to go out to meet them,” Wu said. “They fly very close, and we have to be careful that we don’t fire the first shot in a war.”

Yet Taiwan’s leaders remained curiously low-key. Tsai Ing-wen, the President, welcomed Pelosi and denounced the Chinese military exercises but otherwise carried on as if little were amiss. When the Chinese test-fired the ballistic missiles, she didn’t tell the public that they flew over the island; that became known only after it was announced by Japanese leaders. When a Chinese drone flew into Taiwan’s airspace, Tsai’s government reacted with similar reserve, announcing the intrusion only after videos appeared online showing soldiers throwing rocks at the drone.

Wu, the foreign minister, told me that Tsai was trying to strike a balance between deterring the People’s Republic and exhausting the Taiwanese people by warning them too often. To some Taiwanese, though, her handling of the missile tests amounted to wishful thinking. “When something like this happens and there’s no response, the government looks like it doesn’t know what it’s doing,” Alexander Chieh-cheng Huang, a former Taiwanese foreign-service officer in the U.S., told me. “The attitude is ‘Don’t look up.’ ”

On Kinmen, an outlying island of Taiwan, the Chinese mainland looms so close that you can hear the construction cranes booming across the water. The island, about twelve miles from end to end, sits across the bay from the bustling mainland city of Xiamen. Whereas Xiamen is a place of gleaming high-rises, Kinmen is dotted with low-slung villages and patches of forest; it is famous for kaoliang, a sweet but fearsomely potent liquor distilled from sorghum.

In the nineteen-forties and fifties, Kinmen was the scene of ferocious assaults by Communist China as it tried to seize control. The invading forces, expecting an easy victory, were met with surprising resistance, from fighters dug in behind rows of steel spikes and in cement bunkers along the beach. Frustrated, the Chinese began bombarding Kinmen, flinging thousands of artillery shells across the water in the hope of forcing its people to surrender. When I visited not long ago, an eighty-year-old resident named Lin Ma-teng recalled hearing the shells as a young boy: “I used to hide under my bed.”

The shelling continued for decades. One day in 1975, when Lin was serving in a Taiwanese artillery unit, a shell exploded nearby, tearing off a chunk of his right thigh. He spent a year in the hospital and still walks with a limp. During my visit, he showed me rusting artillery shells that he has piled in his hallway—mementos of the long conflict between the fragile island democracy of Taiwan and the behemoth next door, which has never stopped trying to assert dominion. On the beach near Lin’s house, visitors can still see the bunkers and barriers, where people he knew in his youth fought the Chinese. They’re crumbling now. “Maybe the war is coming back,” he told me. “What would the people of Taiwan do? Jump into the ocean and swim?”

This past summer, the fight for Taiwan flared again. On June 13th, Wang Wenbin, a spokesman for the Chinese Foreign Ministry, declared that the People’s Republic had “sovereignty, sovereign rights, and jurisdiction” over the Taiwan Strait. Under international law, the strait has long been considered an open waterway; Wang was sweeping that away. “Taiwan is an inalienable part of China,” he said. Two weeks later, the People’s Liberation Army announced that it would hold a live-fire exercise seventy miles off the island’s coast. Then, on August 2nd, the House Speaker, Nancy Pelosi, arrived in Taiwan, making her the highest-ranking American official to visit in twenty-five years. As she greeted officials, an American aircraft carrier, the U.S.S. Ronald Reagan, loomed offshore.

Soon after Pelosi departed, the P.L.A. test-fired eleven Dongfeng ballistic missiles, which landed in waters around Taiwan; at least four flew over the island itself. Then the P.L.A. initiated a large-scale naval exercise, arraying warships outside Taiwan’s major ports. “The U.S. has made wanton provocations,” Wang said. That same week, Chinese fighter jets undertook flights down the Taiwan Strait, crossing the “median line,” the customary boundary between the two countries; each time, Taiwanese jets scrambled to confront them.

The crisis passed, but it gave some American officials a sense that a confrontation between the two nuclear-armed superpowers was dangerously possible. “It was scary,” a senior Biden Administration official told me. “Not because we thought the Chinese would invade, but we worried there might be an accident, with unpredictable actors all around.”

China’s leaders seized the moment to say that they were “normalizing” these kinds of encroachments. In the next two months, Chinese fighter jets crossed the median line more than six hundred times. The flights were “very close and very threatening,” Taiwan’s foreign minister, Joseph Wu, told me. Although China claimed that the maneuvers were a response to Pelosi’s visit, Taiwanese officials said that they had almost certainly been in the works for months.

These moves seemed designed to convince the Taiwanese people that their national existence—which grew out of the chaos of the Chinese Civil War, more than seventy years ago—was coming to an end. Physically, too, the provocations took a toll, wearing down the Taiwanese armed forces. “Whenever the Chinese send their planes up there, we have to go out to meet them,” Wu said. “They fly very close, and we have to be careful that we don’t fire the first shot in a war.”

Yet Taiwan’s leaders remained curiously low-key. Tsai Ing-wen, the President, welcomed Pelosi and denounced the Chinese military exercises but otherwise carried on as if little were amiss. When the Chinese test-fired the ballistic missiles, she didn’t tell the public that they flew over the island; that became known only after it was announced by Japanese leaders. When a Chinese drone flew into Taiwan’s airspace, Tsai’s government reacted with similar reserve, announcing the intrusion only after videos appeared online showing soldiers throwing rocks at the drone.

Wu, the foreign minister, told me that Tsai was trying to strike a balance between deterring the People’s Republic and exhausting the Taiwanese people by warning them too often. To some Taiwanese, though, her handling of the missile tests amounted to wishful thinking. “When something like this happens and there’s no response, the government looks like it doesn’t know what it’s doing,” Alexander Chieh-cheng Huang, a former Taiwanese foreign-service officer in the U.S., told me. “The attitude is ‘Don’t look up.’ ”

Taiwan’s defeat would dramatically weaken America’s position in the Pacific, where U.S. naval ships guard some of the world’s busiest sea lanes. Taiwan is an anchor in a three-thousand-mile string of archipelagos, known in military parlance as the “first island chain,” that wraps around the Chinese coast and helps constrain naval vessels heading to open sea. Another senior Biden official told me the Administration is worried that China feels increasingly able to seize the territory it has been coveting for much of the past century. “The Chinese hope that within the next five years or so they will be in a position where we cannot stop them from taking Taiwan,” the official said. “The way they see it, they are building up a sufficient capability to be able to execute an operation, and the tyranny of distance is so great that we wouldn’t be able to stop them.”

When I arrived in Taiwan, I found a place consumed not by the threat of societal extinction but by concerns about Covid. Boarding China Airlines, Taiwan’s national carrier, in Los Angeles, I was met by flight attendants in full-body medical suits and plastic visors, who politely chided me every time my mask fell beneath my nose. In Taipei, the capital, I was driven in a “quarantine taxi” to a “quarantine hotel,” where I was escorted to a room and instructed to stay inside. Meals packaged in plastic and Styrofoam were left at my door, and my windows were sealed tight. I emerged four days later into a flourishing city, with high-speed trains, exquisite restaurants, and masked people rushing between appointments, glancing at their phones. Taiwan sits in a climatological region called Typhoon Alley, and soon after my quarantine ended Typhoon Hinnamnor swept the island with wind and rain. No one was fazed.

I’d expected an embattled nation girding for a fight, but Taiwan seemed too caught up in the stresses and entertainments of prosperous modern life to think much about the enemy next door. In everyday conversation, the China question rarely came up. There were few signs of national preparation: military conscription is mandatory for adult men but lasts only four months. The government is considering adopting a policy that would allow it to mobilize its civilian population, but so far has done nothing. According to American and former Taiwanese officials, Taiwan’s defense posture is guided by a strategy that was devised in the nineteen-eighties, when the Chinese military was weak.

One day, I sat with Liao Chung Lun, a twenty-four-year-old graduate of National Chung Hsing University, where he studied environmental engineering. Liao had just completed his mandatory military training, which he described as something similar to summer camp. During the first month, he said, he and other recruits did pushups, a bit of running, and rudimentary combat drills, like thrusting a bayonet. A handful of times, he fired a gun. Liao told me that the course wasn’t especially rigorous. “Nobody fails out,” he said. His main jobs included collecting the day’s dirty laundry and pulling weeds. “They have really high standards for cleanliness.”

Like most of the young people I talked to, Liao said that he felt thoroughly Taiwanese and had almost no connection to China. But, when I asked him if he was worried about Taiwan’s future, he shrugged. “We’ve been hearing this for years—that the Chinese are going to invade,” he said. For much of Liao’s generation, the fear of invasion has simply lasted too long to feel urgent; like the typhoons, it has faded to background noise.

The struggle for Taiwan dates to 1895, when troops from the Japanese Empire wrested control of the island from China. After Japan’s defeat in the Second World War, sovereignty over Taiwan returned to China, but it would soon be contested again. The Republic of China was then embroiled in a civil war, which pitted government troops loyal to Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek against Communist insurgents led by Mao Zedong. In 1949, Mao won, and the People’s Republic of China was created. Chiang and his allies fled to Taiwan and a handful of other islands, declaring themselves the true representatives of the Chinese republic and vowing to keep up the fight.

In January, 1950, Dean Acheson, President Harry Truman’s Secretary of State, drew a “defensive perimeter,” committing the U.S. to protect a huge part of East Asia against Communist aggression. He left South Korea and Taiwan outside of it; Truman, like others, expected Taiwan to fall before long. But, six months later, North Korean troops invaded South Korea, with help from the Soviets, sparking fears of a wider war. Truman ordered an aircraft-carrier battle group into the strait, and in 1954 the U.S. signed a defense treaty with Taiwan, placing troops and even, for a time, nuclear weapons there.

Chiang had brought with him more than a million mainland Chinese to an island with a population of six million; his political movement, the Kuomintang, dominated Taiwan for more than forty years. An austere and unforgiving autocrat, Chiang declared martial law and repressed dissent. During one savage period, known as the White Terror, some twenty-five thousand civilians were killed and tens of thousands imprisoned. There were no free elections, no free press, and no political parties other than the K.M.T.

For years, Chiang fostered the idea that his was the legitimate government of China, even though it exercised no control over the mainland. The state of war with the mainland was constant; sometimes the two sides shelled each other across the strait. With the world divided by the Cold War, Western governments propped up the notion that Taiwan was the true China. For thirty years, the U.S. maintained diplomatic relations with the Republic of China and not the People’s Republic, and until 1971 Taiwan occupied China’s permanent seat on the United Nations Security Council. In office, Chiang nurtured the dream that his forces would return to the mainland and overthrow the Communists. Taiwanese children born on the island were taught to believe that they were Chinese, regardless of their origins, and that their true homeland lay across the water.

Among the first generation of children who navigated the puzzle of Taiwanese identity was Lung Ying-tai, who grew up to be, through her books and journalism, a crucial advocate for democracy on the island. I met her in Dulan, a vast stretch of forested mountains along the southeastern coast. The area is home to the Amis, one of Taiwan’s Indigenous groups; according to local tradition, the mountains are inhabited by a benevolent god named Malatao. Lung’s house sits on a hillside overlooking Green Island, where political prisoners were held during the years of Chiang Kai-shek.

Lung was born in southern Taiwan in 1952, to parents who had fled Hunan Province during the civil war. Her father, a member of the K.M.T., became a provincial police officer. In school, she was taught the history and culture of mainland China but little about the island itself; the instruction was in Mandarin, rather than in the Taiwanese dialect.

Lung’s connections to the mainland were not abstract: her parents had left a one-year-old son behind with relatives, fearing that he wouldn’t survive the chaos of the exodus. “My mom thought they would be able to go back to get him,” she told me. Taiwan’s laws prohibited any travel across the strait; even exchanging letters could bring a death sentence. As a result, Lung heard only whispers of a brother she’d never met. “I didn’t even know if he was still alive,” she said.

Chiang died in 1975. That year, Lung travelled to the U.S. to study at Bowling Green State University, and she went on to Kansas State University for a Ph.D. in literature. Freed from restrictions on communicating with the mainland, she wrote a letter to her brother; because she did not know where he lived, she scrawled on the envelope his name, Ying-yang, the county where her family had resided, and “the Lungs’ village.” She figured that it would never reach him, but three months later a reply arrived. “It was like a miracle,” she said. “My brother didn’t even know he had brothers and sisters.”

From abroad, Lung became celebrated for her writing about the politics and history of Taiwan and China; she focussed on the predations of the K.M.T. and on the upheavals that broke so many families apart. Her books sold best on the mainland, and a column she wrote appeared in newspapers throughout China. In 1985, she published a withering criticism of the K.M.T.’s rule, “The Wild Fire,” which was influential in the democratization of the island.

After Chiang’s death, Taiwan entered an era of political ambiguity. In 1979, President Jimmy Carter established diplomatic relations with the People’s Republic of China and severed them with Taiwan; the last U.S. troops withdrew from the island. Still, a succession of Presidents continued to pledge support, giving an impression, if not a promise, that America would help defend against a Chinese attack. The U.S. sold weapons to Taiwan and allowed its diplomats to keep an office in Washington, D.C., as long as it wasn’t called an embassy. Taiwanese leaders performed a delicate balancing act, using their relationship with the U.S. to retain independence while also cultivating economic ties with the mainland.

In 1987, Chiang Kai-shek’s son and successor, Chiang Ching-kuo, lifted martial law and began easing travel restrictions. Lung arranged to bring her parents to Hong Kong, where she met her brother Ying-yang for the first time. “He’d become a thin, dark-skinned, slightly bent peasant, denied education because his father had served in the Republic Army,” she said. He spoke a dialect that his family could barely understand.

The next year, the K.M.T. installed Lee Teng-hui, a Cornell-educated economist, as President. Lee moved Taiwan decisively toward democracy but at the same time presided over an improvement in relations with the People’s Republic; Taiwan provided markets for China’s products and investment in its economy, which was largely cut off from the West following the massacre of pro-democracy demonstrators at Tiananmen Square. Four years into Lee’s tenure, unofficial representatives of the two countries met in Hong Kong and reached an understanding—the 1992 Consensus, as it became known—that Taiwan and China were inextricably linked. The K.M.T.’s leaders had given up fantasies of reconquering the mainland; they hoped instead that the two countries, with their shared history and culture, could find a way to coexist until, at some undefined moment in the future, they became one China again.

In 2008, another K.M.T. candidate, Ma Ying-jeou, was elected President on a promise of greater integration. Ma, who trained as a lawyer at Harvard and New York University, told me in his office, “This was my vision—that bringing the two sides closer together would make war impossible.”

It would also help Taiwan prosper. At the time, Western economies were grappling with a steep recession, while China, Taiwan’s largest trading partner, was growing. In the next six years, Ma negotiated dozens of agreements with the mainland. Airlines began running daily flights across the strait, and thousands of Chinese visited Taiwan for the first time. In 2015, Ma met Xi Jinping, the head of the Chinese Communist Party, in Singapore; it was the first such meeting since the end of the civil war. To avoid any awkwardness in the use of official titles, Ma was referred to as “the leader of Taiwan” and Xi as “the leader of mainland China.”

Ma told me that during his time in office Taiwan’s birthrate began to rise, after years of decline. “That’s how hopeful people were,” he said. But the island was restive. Lung said, “As China became more repressive, the Taiwanese people began to feel more and more separate from the mainland.” Lung became Ma’s minister of culture, and initiated programs for Chinese artists, writers, and filmmakers to come to Taiwan. “I especially supported documentary filmmakers in China because they were so critical of the establishment,” she said.

There was also a growing political opposition in Taiwan. In 1986, a group of activists, some of them former political prisoners, had founded the Democratic Progressive Party (D.P.P.), which called for a stronger Taiwanese identity. With democracy flourishing, and a greater share of the population born on the island, a sense of nationhood had taken hold.

In 2013, Ma announced his most ambitious plan, the Cross-Strait Services Agreement, a measure that would have lowered barriers for Chinese to invest in such things as banks, shopping centers, and construction firms. Lin Fei-fan, a graduate student at National Taiwan University, helped lead a revolt. Lin told me he and his allies feared that the law would open Taiwan to a flood of Chinese money and people. “The feeling was that we were going to be swallowed by the mainland,” he said. “And the deals were being made over our heads—we didn’t ask for them.” The following March, Lin and about two hundred other students occupied the parliament building, vowing to stay until the Agreement was shelved and a mechanism was established to allow for public input. Tens of thousands more joined demonstrations in the streets, and after twenty-four days legislators agreed to put the plan on hold.

The Agreement proved to be the apex of coöperation between the two countries. In 2016, Ma’s party was swept from office by the D.P.P., a movement formed expressly to make Taiwan independent. Tsai Ing-wen, the new President, made Lin the Party’s deputy secretary-general. For Lin, the results confirmed that many other Taiwanese felt the same way that he and his fellow-protesters did: “We don’t want to be part of China.”

Reserved and cerebral, Tsai Ing-wen seemed an unlikely national leader. Born in 1956, she was one of eleven children. Her father was a member of the Hakka, a historically marginalized group. Her mother doted on her, making her lunches into her college years. Tsai studied law, earning degrees from Cornell and the London School of Economics, where she wrote her doctoral dissertation on international trade. As a young official, she attracted attention for her role in negotiating Taiwan’s tortuous entry into the World Trade Organization, where it was admitted not as a country but as a “separate customs territory.”

Tsai claimed to dislike the spotlight; in her memoir, she described herself as “a person who liked to stick close to the wall when walking down the street.” Elsewhere in the book, she wrote of the joys of toiling in obscurity: “This is Tsai Ing-wen, always proving herself in the quietest way.” People who know her did not disagree. “She’s most at home with her cats and dogs,” a friend told me.

As a Presidential candidate, in 2015, Tsai said that she supported the status quo in Taiwan’s relationship with China. She passed notes, through Taiwanese academics, to senior leaders in China, telling them that she wanted good relations. In public statements, Chinese officials suggested that those relations rested on her affirming that Taiwan and China were part of the same country.

The prevailing idea in China was that Taiwan would eventually join the mainland, much as Hong Kong had when it ceased to be a British colony, in 1997—an arrangement known as “one country, two systems,” in which a democracy could, at least rhetorically, coexist with a dictatorship. Tsai was faced with a conundrum. Bonnie Glaser, the director of the Asia Program at the German Marshall Fund, who has known Tsai for years, told me that Tsai was under pressure to placate the Chinese but couldn’t call Taiwan and China “one country” without splitting her own party. And she knew that Beijing was wary of the D.P.P. “The Chinese had already made up their minds that this woman was pro-independence to the core,” Glaser said.

In Tsai’s inaugural speech, she declared, “The two governing parties across the strait must set aside the baggage of history.” China’s leaders swiftly broke off contact. “The mainland and Taiwan belong to the same China,” Ma Xiaoguang, China’s Taiwan-affairs spokesman, said. “There is no room for ambiguity.” Tsai was vilified in official news outlets. A piece published by the Xinhua News Agency blamed her policies on the fact that she is unmarried and lives alone. “As a single female politician, she lacks the emotional encumbrance of love, the constraints of family, or the worries of children,” an analyst with the People’s Liberation Army wrote. “Her style and strategy in pursuing politics constantly skew toward the emotional, personal, and extreme.”

In fact, as a public speaker, Tsai was often dull. But she posted regularly on social media, pressing into crowds and posing for selfies with supporters. As she resisted Chinese pressure, her popularity surged. In 2019, when Xi said that he might use force to compel reunification, Tsai issued a sharp retort, insisting that China “must accept the existence” of Taiwan and acknowledge it as a democratic state. “Taiwan absolutely will not accept ‘one country, two systems,’ ” she said. Admirers began calling her Spicy Taiwanese Girl, borrowing a lyric from a popular song.

A pivotal moment came later that year, when Chinese security forces crushed peaceful protests in Hong Kong. Tsai became even more emphatically opposed to integration. Official contact between her government and China’s dropped to nothing, cross-strait travel and cultural exchanges plummeted, and eventually Tsai allowed American Special Forces to come train Taiwanese soldiers. The details of that program, and of many others the Americans are overseeing to help the Taiwanese strengthen their defenses, are kept quiet. “We probably do more diplomatically and more behind-the-scenes stuff with Taiwan than almost any other place—and we talk very little about it,” a senior American official told me.

Although Tsai maintained that she was willing to talk to the Chinese, there seemed to be a growing sense that the time had passed. “The moment we sit down with the Chinese, it’s over,” Lin told me. “There’s only one thing they want to talk about.”

During Tsai’s tenure, Chinese diplomats have worked to deepen Taiwan’s isolation. One by one, Chinese diplomats have persuaded Taiwan’s diplomatic partners to abandon her; the latest, in 2021, was the government of Nicaragua, which had maintained relations with the Republic of China for most of the past century. The senior American official said that the Nicaraguan government could expect to be rewarded with generous Chinese aid. “It’s very transactional,” Glaser told me. Only fourteen countries now have diplomatic relations with Taiwan, many of them island nations like Tuvalu. Under Chinese pressure, Taiwan has been excluded from the United Nations General Assembly and from formal membership in most international institutions, including the World Health Organization.

The result has been an uncomfortable paradox: even as Taiwan has developed a sense of nationhood, much of the rest of the world has pulled away. Earlier this year, President Biden dispatched a group of prominent former officials to reassure Tsai and to assess the situation. One of the officials on that trip told me that he was unnerved by what he saw: “What you notice when you’re in Taiwan is the profound sense of isolation. They’re alone.”

In 2015, two Taiwanese university students, Truman Chen and Sandra Ho, attended a journalism conference in Fujian, China. It was the height of Taiwanese and Chinese coöperation, and the students were obliged to sit through a performance of propaganda tunes like “The Embrace of the Motherland Always Welcomes You.” “It was so silly, we couldn’t stop laughing,” Ho told me. Back in their dorms, she and Chen poked fun at the exercise on WeChat, the social-media platform, and their riffs were a hit.

When they returned home, they kept up their act, imitating the newscasts on CCTV, the state-run Chinese channel. Chen played a straight-faced anchorman, narrating the preposterous reports that appeared onscreen. “Our feeling was that so much of the news was really funny and absurd, and we could tell people what was happening and have fun at the same time,” Ho told me.

Their posts grew into a comic newscast, “Eye Central TV,” which airs several times a week on YouTube; the most popular episodes get a million views apiece. Chen and Ho often taunt Taiwanese politicians, especially for their historic obsession with returning to liberate the mainland; China is referred to as the “occupied area,” with maps of Taiwan’s territory altered to include everything from Fujian to Mongolia. But the absurdities of the People’s Republic supply most of the material. Xi Jinping is referred to as Winnie-the-Pooh and the government as the Red Bandit. A recent segment took aim at Xi’s draconian “zero Covid” policy: video clips showed Chinese health workers, wearing rubber gloves and dressed in suits and masks, performing PCR tests on roosters, crayfish, lake trout, even cabbage. Then a clip rolled of a spokesman for the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs explaining the policy. Chen referred to him as a “male publicist”—Mandarin slang for a male prostitute.

The creators of “Eye-C TV,” like much of its audience, are under the age of thirty-five, and the show is emblematic of Taiwan’s generational divide over ties with China. To Chen and Ho, the People’s Republic is a slightly crazy neighbor, whose main purpose is to provide fodder for jokes. “We don’t feel connected to China, but there is no way for us to say that we are not related to China, because many people’s ancestors are immigrants from there,” Ho said. Chen added, “None of my friends want to be a part of China. We’re different countries.”

In polls, the prospect of unification generally garners single-digit support. But many Taiwanese, particularly older ones, believe that President Tsai’s refusal to appease China is putting them at risk. “The D.P.P. is painting the Chinese into a corner,” Lung, the writer, told me. “The danger is that they’ll conclude they have no options except war.”

On paper, the Taiwanese military is overmatched. It has about two hundred thousand active-duty soldiers, sailors, and airmen; the P.L.A. is thought to have more than two million troops. Ian Easton, a research fellow at the Project 2049 Institute, a China-focussed think tank, told me that Taiwan could mobilize as many as four hundred thousand reservists within seventy-two hours. The trouble is that there is little infrastructure to accommodate a large-scale mobilization, and no weapons. “They are very big, but not very good,” he said.

Taiwanese leaders have so far refrained from establishing any kind of militia to provide guns and training to civilians who could be deployed in a crisis. And while there has been some discussion of extending the period of mandatory conscription to at least a year, that, too, has failed to materialize. Enacting either of those measures would require a substantial political commitment. “No leader wants to be the bad guy and ask people to sacrifice,” Chang Yen-ting, a former deputy commander of the Taiwanese Air Force, said.

As tensions with China have risen, some private citizens have begun acting on their own. One Saturday morning, in the basement of the Chi-Nan Presbyterian Church, in Taipei, I visited a course in first aid and rudimentary civil defense. An instructor showed some sixty concerned civilians how to move a person who has been wounded and how to stanch bleeding; other courses were dedicated to operating two-way radios and preparing to live in community shelters. Several similar groups have formed. One of those who signed up was a woman who asked not to be named, for fear of retribution. She grew up in Taipei, attended college in Hong Kong, and went on to work for a bank there. “When the Chinese came to Hong Kong, they brought in their surveillance cameras and their facial-recognition software,” she told me. “That’s what they want to do here.”

Robert Tsao, a billionaire founder of one of Taiwan’s leading semiconductor manufacturers, U.M.C., pledged more than thirty million dollars to lay the groundwork for a territorial-defense program. Tsao was born in Beijing and did business with China as he built his fortune, but, since the crackdown in Hong Kong, he has begun referring to Chinese leaders as a “gangster mafia.” He told me that he envisioned a force of three million women and men; his funding would supply a down payment on housing and firearms training. “I don’t care if the government isn’t ready,” he said. “We have to act.”

President Tsai is constrained in part by pockets of pro-unification sympathy—particularly among her rivals in the K.M.T. In August, Andrew Hsia, a K.M.T. leader, travelled to China and met with government officials—one of the first such meetings in years. Hsia was vilified by Tsai’s supporters for the meeting, but he told me that his Chinese interlocutors were frustrated that they had no one to talk to in the Taiwanese government. “It’s a dangerous situation,” he said. “There’s no dialogue. That’s when accidents happen.”

The most powerful constituency for closer ties with China is the business community. Since the nineteen-eighties, Taiwan has invested tens of billions of dollars in China, and thousands of companies have opened operations there. Among them are some of the largest and most successful businesses in the world, including Foxconn, whose factories on the mainland assemble millions of cell phones a year. More than two hundred thousand Taiwanese live in China, many of them working in tech jobs. Taiwan is a net beneficiary of this economic relationship, with a trade surplus of a hundred and four billion dollars last year.

Many businessmen with operations in China are close to the K.M.T. and hold more positive views of China. Sheen Ching-jing was born in China in 1947 and fled to Taiwan with his parents two years later. He returned in the early nineteen-nineties and built the Yangzhou Core Pacific City Development Co. With more than six thousand employees, Sheen’s company has constructed apartment complexes, shopping centers, and homes. Sheen told me that good relations with China were essential to Taiwan’s prosperity. “This is an era of economics,” he said. “We share the same culture. We are of the same tribe. There’s no reason for us to be separate countries.” The widespread opposition to unification would inevitably fade away, and military force would be unnecessary, Sheen said: “The question will be naturally resolved.”

Some Taiwanese businessmen told me privately that Chinese officials had pressured them to avoid political positions that ran counter to China’s foreign policy. One businessman, who called himself Winston, said that China favored K.M.T. candidates—and made it clear that supporting the D.P.P. would invite punishment. Winston, who oversees an operation with thousands of employees on the mainland, said a government official approached him after discovering that one of his employees had contributed to a pro-independence Presidential candidate in Taiwan. The official threatened heavy punishment if the donations continued. “It was very sensitive,” Winston said.

During the 2020 election campaign, Winston recalled, his company’s leaders declined a request from President Tsai to appear with them in Taiwan, for fear of angering the Chinese: “It put us in a very tricky position.” He told me that his operations in China were under constant threat of inspections and fines, and that it was sometimes necessary to bribe officials to keep them from causing trouble. “We are dealing with people who are trying to make as much money as possible in the jobs they have, before they are moved out,” he said. “It’s a very difficult environment.”

The K.M.T. says that it is committed to preserving Taiwanese sovereignty. But some of its leaders have grown remarkably close to China. In May, Hung Hsiu-chu, a former K.M.T. chairwoman, toured Xinjiang, where Western governments have accused the Chinese government of committing genocide against the Uyghur minority and maintaining an archipelago of forced-labor camps. Speaking to Chinese media afterward, Hung dismissed claims of genocide, saying that she saw only “bright smiles on everyone’s faces, full of hope for the future.” She didn’t notice any Uyghurs working against their will, either: “If they are, why do they all show satisfied looks on their faces?”

Suspicions abound that pro-Chinese leaders have quietly accepted money from the mainland. One of them is Zhang Xiuye, a native of Shanghai who married a Taiwanese man and, in 2018, ran for a seat on the Taipei City Council. That October, she and a colleague in the Patriotic Alliance Association, which advocates unification, were charged with accepting sixty-two thousand dollars from a source in China, apparently to help their candidacies. Both denied wrongdoing; Zhang posted bail and disappeared, presumably to the mainland. “We suspect the Chinese are doing a lot of this,” Syu Guan-ze, an independent researcher, told me. “But it’s nearly impossible to track all the money flowing into Taiwan.”

At a conference in Beijing in 2019, a senior member of the Chinese Communist Party exhorted Taiwanese media executives to advance China’s plan for the island. “We want to realize peaceful unification—one country, two systems—and we need to rely on the joint efforts of our friends in the media,” the Chinese leader said, according to a video of the meeting. “I believe you understand the situation. History will remember you.”

Much of the suspicion about Chinese efforts to co-opt the media has fallen on Tsai Eng-meng, a Taiwanese billionaire who built a sprawling conglomerate, called Want Want, of snack-food factories, hotels, and real estate on the mainland. Beginning in the two-thousands, Tsai bought several large Taiwanese media properties, including the China Times newspaper and CTi TV, which became known for a sharply pro-China slant. In 2019, it was reported that Want Want had received more than half a billion dollars in subsidies from the Chinese government since 2004; during the most recent Presidential campaign, CTi TV devoted nearly three-quarters of its coverage to the K.M.T. candidate. “It’s an outlet for Chinese propaganda,” K. C. Huang, the head of TAWPA, an organization dedicated to fighting corruption, said. In 2020, the Taiwanese government declined to renew the broadcasting license for the company’s news network, after receiving hundreds of complaints from citizens.

Misinformation is ubiquitous on Taiwanese social media. This summer, an audio recording widely suspected of coming from China gave instructions on how to prepare for an impending invasion. “Everyone must stay away from military facilities, sit quietly in their homes, and wait for liberation,” a Chinese-accented voice said. “If you have children in the Army, be sure to tell them if the People’s Liberation Army attacks Taiwan to hand over their guns and they won’t be killed.”

In 2013, Chinese construction crews arrived at a shoal in the South China Sea known as Mischief Reef. It was a speck in the ocean—so shallow that at high tide it disappeared below the water—but that didn’t last. The Chinese crews began piling sand atop the reef, and eventually poured acres of concrete to build it into an island—attempting to create a new political entity in one of the world’s busiest shipping corridors, on the southern approach to Taiwan. Mischief Reef was also claimed by the Philippines, which sued China in the International Court of Arbitration. But the Chinese crews carried on, even firing water cannons at Filipino boats sailing to a nearby reef. Within a few years, they had built a runway and brought in radar and anti-aircraft missiles, along with troops to man them; over time, two more artificial islands were fully militarized.

The construction was part of a long-running effort to claim jurisdiction in the South China Sea, which is rich in fishing beds and oil deposits. For decades, China’s government has been declaring that tiny spits of land in the sea are in fact islands, entitled to territorial waters that extend out for miles. The Chinese have made more than two hundred such claims, giving them jurisdiction over international waters and making it increasingly difficult for other nations to operate. In 2016, the International Court of Arbitration ruled that the claims had no validity. The Chinese government ignored the ruling, which the vice foreign minister dismissed as “a scrap of paper.”

On September 1, 2021, China declared that any foreign vessel sailing in the territorial waters of the reclaimed reefs and shoals would be required to identify itself. The U.S. refused. As a former senior naval officer told me, “We made it absolutely clear that we weren’t going to abide by that.” A week later, an American destroyer called the U.S.S. Benfold sailed past Mischief Reef without providing identification. Chinese forces went on high alert, and the People’s Liberation Army declared the ship’s presence “the latest iron-clad proof of attempted U.S. hegemony and militarization of the South China Sea.” The U.S. Navy said that the mission was intended to “demonstrate that the United States will fly, sail, and operate wherever international law allows.”

As China stepped up its claims in the Pacific, Western leaders responded. In September of 2021 alone, the U.S. Navy sent aircraft carriers, destroyers, and other warships into the waters around Taiwan or the South China Sea at least six times; the British, at least twice. The next month, ships from the U.S., the U.K., Canada, New Zealand, and Japan gathered in the Philippine Sea for a sprawling multinational naval exercise, one of the largest since the end of the Cold War.

This year, the U.S. has sent warships into the Taiwan Strait or the South China Sea seventeen times and has routinely sent aircraft to patrol there. The naval activity has sometimes been so intense that each side appeared to be reacting to the other. A former senior American naval officer insisted that this wasn’t the case, as the Navy planned each mission weeks in advance. “I think they are reacting to us,” he said. Whenever Americans have appeared, a Chinese vessel or aircraft has invariably come to shadow them.

Occasionally, the encounters have been humorous. In 2015, a U.S. Navy reconnaissance plane was patrolling the South China Sea when it received a radio message. “This is the Chinese Navy,” a voice said in heavily accented English. “Please go away quickly in order to wrong judgment.”

An American officer gave a carefully parsed response: “I am a United States military aircraft, conducting lawful military activities outside national airspace.”

The voice over the radio replied, “Meow.” It was followed by a series of mysterious beeps: the sound of Space Invaders, the nineteen-seventies video game.

In 2020, the Chinese military issued a harsher provocation: a propaganda video, in which nuclear-capable H-6K jets carried out simulated missile attacks. In the video, which the P.L.A. titled “The God of War H-6K Goes on the Attack!,” the warplanes strike what appears to be Guam, the home of Andersen Air Force Base, one of a handful of major U.S. bases in the Pacific. The ground erupts; a block of waterfront warehouses bursts into a fireball, and then a column of smoke rises toward the planes. American observers responded bluffly to the simulation. “We could have killed them six times,” a U.S. military officer told me. Still, China’s belligerence reflected how the balance of military power had shifted since the late nineties, when the two countries got into a dispute over Taiwan, and China was forced to give way.

It began in 1995, when President Lee Teng-hui sought a visa to the U.S. to deliver a speech at Cornell. The Clinton Administration at first refused, but after an uproar in Congress it agreed to grant him one. The Chinese leader, Jiang Zemin, enraged by what he regarded as Lee’s show of independence, ordered missile tests near the island and instructed the P.L.A. to stage military exercises, one of which mimicked an amphibious assault. President Clinton responded by sending a Marine landing ship and two other warships into the Taiwan Strait, followed a week later by an aircraft carrier.

Jiang backed down, but the crisis wasn’t over. The next March, after Lee declared his intention to enter Taiwan’s first free Presidential election, Jiang ordered new missile tests, along with further exercises. This time, Clinton responded with even greater force, sending two aircraft-carrier battle groups into the waters near Taiwan. Amid the crisis, thousands of Taiwanese requested visas to flee the island, and the stock market plummeted. But Jiang backed down again. “The Chinese were humiliated,” a former senior official in the Clinton Administration told me. “They vowed, ‘Never again.’ ”

Since then, China has undertaken an ambitious military buildup that has brought its conventional forces to near-parity with the United States’. The Chinese Navy is now the largest in the world, and, as the U.S. Navy prepares to decommission more of its own ships, the gap is expected to grow. China’s ships and submarines are widely regarded as less effective than their American equivalents, but the Chinese are rapidly modernizing.

China’s growing capabilities have coincided with an increasingly aggressive approach to foreign policy. For years, its leaders seldom boasted of their country’s military prowess, following the dictum of the former leader Deng Xiaoping to “hide your strength, bide your time” as the economy grew.

Since becoming the head of the C.C.P., in 2012, Xi Jinping has abandoned that precept. He set no deadline for bringing Taiwan into China but suggested that he intended to be in office when it happened. The Taiwan question, he said, “cannot be passed from generation to generation.” Last year, in a speech commemorating the hundredth anniversary of the Communist Party, he warned, “The Chinese people will never allow any foreign forces to bully, coerce, and enslave us. Whoever attempts to do that will surely break their heads on the steel Great Wall built with the blood and flesh of 1.4 billion Chinese people.”

Xi’s reëlection as Party chairman in October appeared to herald a new era of assertiveness. He emerged from the Party Congress, held in the Great Hall of the People, in Beijing, stronger than ever; he purged his main rivals in the Politburo and its Standing Committee, many of them market-oriented technocrats, and elevated loyalists, most of them drawn from the military and security establishment. In one highly visible moment, Xi looked on as his aging predecessor, Hu Jintao, was roughly escorted from the stage. Several of Hu’s allies, most of them relative moderates, were soon expelled from the Party.

In his speech to the Party Congress, Xi warned of “dangerous storms” ahead and ordered leaders to prepare for an era of “struggle,” a word that was edited into the Party’s charter in seven places. Phrases that suggested stability, like “peace and development will remain the themes of the era,” were removed from a report accompanying the speech. “Our country has entered a period when strategic opportunity coexists with risks and challenges,” Xi told the Party’s leaders. “The world has entered a period of turbulence and transformation.”

Western experts say that Xi’s ultimate ambition is for China to supplant the United States as the world’s preëminent power. His goal is what he calls China’s “great rejuvenation,” the recovery of national power, pride, and territory that fell away in the nineteenth century, with much of it surrendered to the West. Making Taiwan part of China, Xi has said, is one of his project’s crucial chapters.

For many China specialists in the West, the speech was a watershed. “There are no longer any checks on Xi’s power within the system,” Matt Pottinger, who served as deputy national-security adviser under President Donald Trump and is now a visiting fellow at the Hoover Institution, told me. “Any checks that now exist are external to China. Inside the system, Xi can do what he wants, including start a war.”

Several times a year, David Ochmanek, a former Pentagon official who is now at the Rand Corporation, in Washington, assembles Navy and Air Force officers and officials to conduct war games between the U.S. and China over Taiwan. The participants gather around a large map showing forces arrayed across the region. Those playing the Chinese leaders are steeped in knowledge of China’s decision-making; all have access to the U.S. government’s best information. “The war games are so real that the participants are exhausted and stressed out—they take them very seriously,” Ochmanek told me.

The simulations take many forms, but usually start with a crisis, like the election of a pro-independence President of Taiwan, or with an outright invasion. Many of them end badly for the United States, Ochmanek said: “We usually lose.” Sometimes the Chinese military is able to keep the U.S. Navy at bay and capture Taiwan. Sometimes the Chinese sink U.S. aircraft carriers. This puts the burden on the participants who are mimicking American officials. Do they give up, or escalate? Do they strike China itself? “Sometimes, when the U.S. attacks the Chinese mainland, the Chinese attack Alaska and Hawaii,” he said. “The losses are very heavy.”

It’s not always so dire, Ochmanek said. In some cases, the United States prevails. And even the games that the U.S. loses are not necessarily reflective of how a war would unfold in real life; the main purpose is to evaluate American vulnerabilities. “We learn a lot from these,” Ochmanek said.

Like the war games, almost everything about a potential war with China over Taiwan is theoretical. For the Americans and the Taiwanese, gauging whether and how a war might start involves assessments of each country’s capabilities and objectives, as well as some calculation of the costs that each side would be willing to bear. For American policymakers, that means trying to determine what is required to dissuade China from attempting to change the status quo by force, or, if it does, how to make any war so painful that China would stop without achieving its goals.

American and Taiwanese experts agree that an invasion of Taiwan would be a colossal gamble for the Chinese leadership. A full-scale invasion would likely begin with cyber and missile attacks on Taiwanese military infrastructure, and possibly with an assault by airborne troops. But eventually an invading force of tens or possibly hundreds of thousands of soldiers would have to cross a hundred miles of water, capture the island’s difficult terrain, and sustain an occupation, presumably while under constant attack.

In testimony before Congress last year, Admiral Phil Davidson, then the commander of the Indo-Pacific Command, expressed concern that China could try to take Taiwan before 2027—the year its military modernization is scheduled to be complete. “I think our conventional deterrent is actually eroding,” he said. “I worry that they are accelerating their ambitions to supplant the United States and our leadership role in the rules-based international order, which they have long said that they want to do by 2050. I am worried about them moving that target closer. Taiwan is clearly one of their ambitions before then.”

Some American officials and experts believe that China’s advantages will begin to wane later in the decade. A new generation of U.S. defense improvements is scheduled to come online, and America’s defense industrial base, now attenuated, will be revived—or so goes the hope. Many of the same experts believe that China might be entering a long-term economic slowdown, brought on by a rapidly aging population and a maturing economy. “My sense is that the window is opening now, and that it won’t be open forever,” Elbridge Colby, a Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense under Trump, told me.

Taiwanese officials say that they are determined to repel an invasion on their own. “We think we would win,” Wu, the foreign minister, told me. But almost no one outside Taiwan believes this. “There is no scenario in which Taiwan can defend itself,” Oriana Skylar Mastro, a fellow at Stanford University and a strategic planner for Pacific Command in the Air Force reserves, told me. A more realistic goal would be to slow down a Chinese invasion, in order to give the U.S., if it chooses to intervene, time to marshal its forces and cover the vast distances to get there. A senior American military officer told me that Taiwan would have to hold off the Chinese for about six weeks. “We think it’s in our favor if it takes forty-five days,” the officer said.

China’s goal would likely be to seize Taiwan as quickly as possible, to present the U.S. with a fait accompli. According to American officials, Beijing worries that it would be unlikely to win a protracted conflict, as the U.S. gathered its allies and revitalized its industrial base. “The longer it goes, the more difficult it gets for the Chinese,” Mastro told me.

For years, Taiwan’s plan for its defense was to attack the mainland bases that would support an invasion. “The strategy is to go to the origin,” Chang, the former deputy commander of the Taiwanese Air Force, told me. The Taiwanese military maintains a formidable conventional force, consisting of fighter bombers, cruise missiles, and anti-ship missiles. But Taiwan’s strategy was designed in the years when its military was closer to parity with China’s. Lee Hsi-Min, who served as chief of the general staff of the Taiwanese military until he retired in 2019, told me that he had pushed for reform without success. “The government didn’t listen to me,” he said.

As China’s capabilities have raced ahead, American officials have begun prodding Taiwan to rely instead on a defensive “porcupine strategy,” which would aim to slow down an invading force using sea mines, anti-ship missiles, and other inexpensive weapons. Taiwanese defense officials have resisted, according to officials in both countries. Earlier this year, Taiwan asked to buy a number of American MH-60R Seahawk helicopters, used for hunting submarines. The State Department rejected the request, which officials considered emblematic of the old strategy. “They’re stuck in the nineteen-eighties,” the senior American official told me.

This year, as pressure from China has increased, the Taiwanese government has acted more urgently. The legislature has approved eight billion dollars in emergency defense spending, for such things as drones, anti-ballistic-missile radar, and patrol boats, all made domestically. But these programs will take time. Until then, the biggest obstacle to preparing Taiwan for a conflict appears to be supplies from the United States. Taiwanese officials told me that they were waiting on the delivery of fourteen billion dollars’ worth of military hardware, including scores of sea mines and anti-ship missiles—the very weapons the Americans have been urging them to buy. One reason, officials say, is that U.S. warehouses have been stripped bare by the conflict in Ukraine. “The Ukraine war has showed us that we don’t have the ammunition stocks to sustain a medium-sized war,” the senior Administration official said. “We don’t have the industrial base.” But Pottinger noted that the demands of supplying Ukraine didn’t explain all the delays: “Stingers and Javelin anti-tank missiles are going to Ukraine, but Harpoon anti-ship missiles are not. The Pentagon procurement system is so screwed up and totally bizarre. Our procurement is asleep. Saudi Arabia is in line to receive the Harpoons before Taiwan. We are not arming ourselves or our friends for the most dangerous fight.”

The biggest question of all is whether America would intervene. Since the early nineteen-eighties, the U.S. has had no legal obligation to defend Taiwan, but, because the American Navy was overwhelmingly dominant, the question wasn’t urgent. As China has grown more powerful, and Xi’s rhetoric more threatening, the matter has become more acute. In recent months, Biden has publicly promised on four occasions to defend Taiwan. Biden’s statements buoyed Taiwanese officials—“fourth time!” one texted me after the latest pledge—but White House officials say publicly that American policy remains unchanged.

The Biden White House seems sharply aware of the consequences of failing to insure Taiwan’s independence. Allowing the island to fall would give the Chinese Navy unrestricted access to the open oceans, as well as effective dominance in the sea lanes of the western Pacific, through which more than three trillion dollars’ worth of goods passes each year. It would also signal to America’s democratic allies in the region—including South Korea, Japan, and the Philippines—that the U.S. could not protect them. Many of the pro-Western countries nearby are under pressure from China as it is. “China is influential in the region, but it is not trusted,” Bilahari Kausikan, a former senior Singaporean diplomat, told me. “Once you display animosity in a naked way, people don’t forget it.” He added, “The leaders in Southeast Asia want American leadership.”

But that doesn’t mean these countries would provide assistance if the U.S. went to war with China. Neither Japan nor South Korea—which have formidable militaries, and which host large American bases—have committed to helping. “With the Japanese, even an attack on the U.S. base in Okinawa would not necessarily trigger self-defense,” Mastro told me. The concern is partly that the U.S. would not win a fight against China. The irony, Mastro said, is that a Japanese decision to join in would likely be decisive. “We would win every time,” she said.

A war to defend Taiwan would put the United States in direct conflict with the People’s Republic of China for the first time since the Korean War, when tens of thousands were killed in face-to-face battles. U.S. officials won’t discuss their battle plans in detail, but experts say that an American response would almost certainly involve missile strikes on the Chinese mainland. “Hundreds of thousands of people would die,” Mastro said.

Likewise, experts say that if the Chinese invaded they would probably attack American bases in Guam and Japan, as they try to keep the Navy at bay. The U.S. military would likely strike back hard and fast, the senior American official said: “We would destroy a lot of their assets immediately.”

But some experts believe that America’s strategy, organized around aircraft carriers, has grown dangerously obsolete—that carriers, while capable of delivering enormous firepower, are increasingly vulnerable to attack. In some of the scenarios that strategists have explored, American carriers could be attacked by Chinese hypersonic missiles that can damage ships even if they’re intercepted. These strategists imagine something akin to the episode in 1905, during the Russo-Japanese War, when the Imperial Japanese Navy sank almost the entire Russian Pacific fleet in a single battle. “If we don’t change, we will lose,” Lieutenant General S. Clinton Hinote, a deputy chief of staff at the Pentagon, told me.

There’s another concern for some American officials: that the United States does not have the industrial capacity to sustain a longer war with China, which maintains the world’s largest steel and shipbuilding industries. “Who can rebuild their losses faster?” a senior military officer said. “Who can lay steel for new ships? Who can make carbon fibre faster for new aircraft? Aircraft carriers? Against China, we’re not in a position to take one for one.” The problem, experts say, stretches across the spectrum of manufacturing capability; a recent report by the Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies, an American research firm, said that, in a war with China, the U.S. Air Force would run out of advanced long-range munitions in less than two weeks.

China has its own reasons for caution. Richard Chen, a former deputy defense minister of Taiwan, told me that the most basic obstacle to an invasion was geography. Only about a dozen of Taiwan’s beaches are suitable for landing soldiers and material in large quantities; the water is too shallow for ships to come in close, and the beaches are too narrow to hold more than a battalion—about eight hundred troops—at a time. The beaches that might accommodate larger numbers lie in underdeveloped areas hemmed in by mountains and jungle. “Invading Taiwan would be a disaster for them, and I think they know it,” Chen said.

Some experts believe that, for Chinese leaders, the risks and uncertainties of starting a war are still too great. “My sense is that the Chinese don’t know what they don’t know—and that is the primary deterrent right now. They cannot, with confidence, predict the outcome,” an American naval officer told me. “If the generals tell Xi Jinping, ‘If you invade Taiwan, you’re going to lose one and a half million members of your armed forces,’ then Xi can decide whether that is a price he is willing to pay.”

But Chen believes that China could try to strangle Taiwan without invading. The island, he said, is vulnerable to a blockade, because so much of what it needs must be imported. The most glaring concern is energy: Taiwan’s power plants run almost entirely on liquefied natural gas and coal. Taiwan has no more than eleven days’ worth of gas in reserve, and about six weeks’ worth of coal. In addition, Taiwan imports two-thirds of its food. “In two weeks, Taiwan would start to go dark,” Chen told me. “No electricity, no phones, no Internet. And people would start to go hungry.” Chen said that the U.S. could protect cargo ships travelling to Taiwan, but he expressed skepticism that such an arrangement would last very long. “The U.S. Navy is going to escort ships into Taiwanese ports?” he said. “For how long? Months? Years?”

If China imposed a full naval blockade, it would constitute an act of war under international law. But a more targeted measure—stopping gas and oil tankers, or blocking arms deliveries—would be enough to cripple Taiwan. Dan Patt, a former deputy director at DARPA and a fellow at the Hudson Institute, in Washington, believes that this would pose the most difficult challenge for American leaders hoping to rally a response. “If it’s not happening on YouTube or social media, there won’t be anything for people to see,” Patt said. “Do you think American voters are going to want to go to war over a commercial cargo vessel being stopped on its way to Taiwan?”

China is also vulnerable to a blockade: it imports more than seventy per cent of its oil from the Persian Gulf via the Strait of Malacca, a narrow waterway that could be blocked with relative ease. Other routes, through Indonesia, would be slower and more expensive. But China has a hundred-day supply of oil, and much of the shortfall could be made up by Russia. “China could last a long time,” Mastro told me.

A larger concern is feeding the populace. China is the world’s largest importer of food, especially from the United States. Peter Zeihan, a demographer who has written extensively about China, told me that a cessation of imports would likely result in famine. “A war with the U.S. would be the end of China as a modern state,” he said.

One of the most important deterrents to war is Taiwan’s role in producing semiconductors. Seventy per cent of the world’s most advanced chips are manufactured there, many of them at the Taiwanese Semiconductor Manufacturing Company. “Banks, iPhones, laptops, cars—almost every piece of modern equipment has a chip from Taiwan,” an executive in the industry told me. “A world without Taiwan is a world back to the Stone Age.” America has purchased some three hundred billion dollars’ worth of chips from Taiwanese factories in the past twenty years. “Apple, Dell, Google—they wouldn’t know how to function without them,” the executive said.

China is similarly reliant on the highest-end chips produced in Taiwan; it doesn’t have the equipment or the expertise to manufacture them. If China seized control of Taiwan’s semiconductor factories, it could conceivably force local workers to run them. But the factories depend on a constant flow of Western material, software, expertise, and engineers, without which production would cease in a matter of weeks. Pottinger told me, “If the Chinese took the factories, there’s no way the West would help run them.” The industry executive wasn’t so sure, given the harm that their loss would do to the global economy. “It’s mutually assured destruction,” he said. Colby, the former official in the Trump Defense Department, went so far as to suggest that perhaps it was best for the U.S. to destroy the plants itself: “If we’re going to lose them, we should blow them up.”

Some Western experts fear that a Cold War dynamic has developed, in which the United States, trying to deter what it sees as aggressive behavior, is taking steps that seem aggressive to Chinese leaders, who then take their own steps to deter the U.S. This year, as China squeezed Taiwan, the Biden Administration took two steps that Chinese leaders are likely to regard as extremely hostile.

The first was a decision, in October, to ban sales to China of sophisticated semiconductors related to A.I., supercomputing, and chip manufacturing, if any part of them is produced in the U.S. Biden officials have said that the measure, which will likely prevent Beijing from buying billions of dollars’ worth of microchips, was intended to curb China’s military modernization. “These are unlike any export regulations we’ve ever had,” Patt, the former DARPA official, said. How will China react? “If you’re China, one reason not to invade Taiwan is that you have a good relationship with the Taiwanese, and they supply a lot of high-end technology,” Patt said. “The Chinese might not want to go to war, but they might be tempted to escalate.”

The second measure, now working its way through the American bureaucracy, would provide Taiwan with some ten billion dollars’ worth of advanced weaponry and training. In the past, Taiwan paid for most of the weapons that the U.S. supplied; under the proposal, the U.S. would give Taiwan money to cover the purchase. “The Communist Party could decide that this is a red line,” Patt said. “They could decide to quarantine all ships carrying American weapons to prevent them from entering Taiwan. What would we do then?”

An open confrontation would have enormous implications. “A war would fundamentally change the character and complexion of global power,” Pottinger said. “If China loses, it could lead to the collapse of the Party and the end of Xi. If Taiwan falls, we are in a different world, where the tide of authoritarianism becomes a flood.” Once engaged, a fight would be difficult to control. If leaders on either side began to believe that they were losing, they could feel pressure to escalate; China might attack Americans overseas, and the U.S. might intensify attacks on the Chinese mainland. Countries throughout the region, and perhaps the world, would be forced to decide whether and how to join the fight.

Even a minor crisis over Taiwan would likely spur large increases in the cost of insurance for ships in the area, potentially driving up the price of many goods in ways that would ripple through the world economy. Ryan Hass, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution and a former diplomat in China, told me, “China’s economy is sagging—there’s low consumption right now, and the principal driver of growth is exports. Would they want to destroy maritime insurance by making it impossible for ships to flow in and out of China? They’d be shutting down their own economy.”

In the Ukraine conflict, the West has had some success imposing sanctions on Russia. Christopher K. Johnson, the head of China Strategies Group and a former China analyst for the C.I.A., said that the Chinese are concerned about sanctions but believe that the U.S. can go only so far without harming its own businesses: “My sense is that Xi and the Politburo have decided that there is no way the West would dare to enact the types of comprehensive financial sanctions they have on Russia.”

Pottinger believes that if there is a war it will be because Xi misreads the conditions. “Xi has huge ambitions,” he told me. “But he has not shown himself to be a reckless gambler. He calculates.” Good bets require precise assessments of risk, though, and it is not clear that Xi is able to make them. “Information is like oxygen,” Pottinger said. “The higher up you go, the thinner it gets. Xi lives on the summit of Mt. Everest.” His officials are unlikely to give him bad news, and his American counterparts are unable to reliably communicate with him: “We came to the determination during the Trump Administration that messages we were sending through diplomatic channels were not reaching Xi. The Biden Administration has come to a similar conclusion.” The senior Administration official told me that the hotline between the two countries is unreliable, because sometimes the Chinese don’t pick up.

In October, Antony Blinken, the Secretary of State, said that China had made “a fundamental decision that the status quo was no longer acceptable and that Beijing was determined to pursue reunification on a much faster timeline.” In recent months, China has begun integrating its fleet of civilian ferries, thought to number in the thousands, into military command. Its army has been staging exercises that feature amphibious invasions, practicing air drops for large numbers of ground troops, and moving military formations on railroads to Fujian Province, which sits just across the Taiwan Strait. The practical effect of these moves is to make it harder to tell the difference between an exercise and the real thing. “That’s the problem with these military exercises—you just extend them and extend them, you normalize them,” Mastro said. “To figure out what they are doing, we are forced to look at much smaller stuff. Are they stockpiling plasma? Are they moving forward medical supplies?” In the Biden Administration, the concern is that the Chinese will abruptly turn an exercise into an invasion. The other Administration official explained the fear: “At some point, they’ll decide, ‘We have to do this,’ and they’ll just look for a casus belli.”

But Johnson suggested it was dangerous to read these incursions as evidence that the Chinese were planning an imminent invasion. “As Marxists, they believe in the value of agitation and propaganda,” he said. “The goal is to wear down Taiwanese resolve and our willingness to intervene. They don’t mind if takes years or a decade.”

Both sides are caught—seemingly unable to back down without appearing to concede. Ryan Hass, the former diplomat, said, “China has a strategic dilemma. They’re frustrated by the status quo, and they’re probing for ways to change it. But taking big, bold actions would come at an extraordinary cost to them. You can’t eliminate the possibility that they would be willing to pay that cost, and so we have to be prepared for it. But if you accept the proposition that war is inevitable, and we must do everything we possibly can to prepare for it now, then you risk precipitating the very outcome that your strategy is designed to prevent.”